Over one hundred years ago, Solomon Schechter was a professor of Talmudic and Jewish studies at Cambridge University in England. Two Protestant women sister spinsters brought to him scraps of ancient Hebraic documents that were originally in the geniza (a storage vault where decaying books, manuscripts and other Hebrew and Judaic artifacts are placed for eventual burial and so that they not be treated as ordinary waste or garbage) of the old main synagogue in Cairo, Egypt. When Schechter deciphered the documents brought to him he realized that he was on to something big. He spent considerable time, effort and scholarship on developing and exploring this treasure trove of Jewish tradition lodged for centuries in the document preserving dry desert air ofEgypt. His years of effort and later publication of many of these valuable documents gained him and Cambridge worldwide fame in the Jewish and general scholarly world.

Schechter’s fame as the “discoverer” of theCairogenizah linked his name inextricably with that genizah and eventually led to his appointment as chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, inNew York City, the training institution for the leadership of the American Conservative movement. Since then for the past century it has been accepted wisdom that the credit for the discovery and development of theCairogenizah belongs to Professor Solomon Schechter.

However as is true with much accepted wisdom in our world, the facts do not quite match the reputation or legend. There is a fine Jew in Petach Tikvah by the name of Leshem who is a descendant of a famedJerusalemscholar and antiquities dealer by the name of Yosef Shlomo Wertheim.

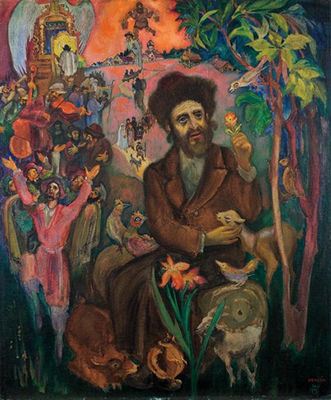

In the middle of the nineteenth century Wertheim left his home in Central Europe and came to live in Jerusalem. Wertheim was a scholar of note, a piously observant Jew, with the visage and appearance of the traditional Orthodox Jew of nineteenth centuryEurope. Wertheim was a noted collector and dealer in Judaica and Hebraica and a publisher of ancient Jewish manuscripts, and traveled extensively in his career pursuits. Decades before any fragments of theCairogenizah reachedCambridgeand Schechter, Wertheim visitedCairoand obtained documents from the genizah. In fact, Wertheim sold to the two English sisters when they visited theHoly Landthe fragments of the genizah that they later brought to the attention of Solomon Schechter. Though they never met personally, it was Wertheim who inadvertently launched Schechter on his genizah expedition and it was Schechter who gained world-wide scholarly credit for theCairogenizah finds. Wertheim was aware of the credit due him regarding theCairogenizah and taken from him by Schechter. In a publication of a work discovered and edited by Wertheim later in his life, Wertheim commented with some sadness about people decorating themselves with a cloak that does not really belong to or fit them properly. He was especially referring to theCairogenizah and Schechter’s fame though he did not refer to him by name. There is always a sense of being violated somehow when someone else reaps the glory for one’s own personal achievement.

This hurt comes through loud and clear in Wertheim’s written words.

Of course, academia and the world of scholarship is many times a desert littered with the bones of plagiarized works, of mentors taking credit for the work of their assistants and students and of out and out fabrications of facts and events. Dr. Schechter certainly deserves credit for his scholarly work on the contents of the Cairo genizah. But so does the little-known, pious Jew of Jerusalem, Wertheim, who first appreciated its contents and brought them to the attention of those who would make its treasures available to the world of Jewish scholarship.