In the early 1700s there existed in Eastern Europe groups of people called Penitents, pious who went from city to city in the hopes of spreading their piety. They were people who felt they had to do public penance for sins they had committed. Often their behavior included whipping themselves and drawing themselves into a frenzy until they drew blood. They tended to attract a great deal of riffraff. Instead of being a pious group, they became synonymous with immorality, theft, murder and illicit behavior. Finally, they were banned by the government.

In the world of Eastern European Jewry, there also were groups who traveled from town to town to inspire the masses. They did not self-flagellate, but as penance for their sins they never slept twice in the same bed. They subjected themselves to suffering, hunger and pain – often leading to early death. Nevertheless, they were viewed as holy people.

Most of these people delved into practical Kabbalah. They wrote and distributed amulets to people who had problems and who had waited for them to come to town. These holy people served especially in the smaller Jewish communities where there were no great scholars, and where visitors rarely came. When a band of holy people appeared – or one holy person – it left an impression that could last a lifetime.

Even though one can find veiled criticisms of them from many of the rabbis of the time, they gained great popularity. Few were willing to criticize them openly and they were given a wide berth.

Rabbi Yaakov Emden records an event at the time involving someone named Rabbi Judah HeHasid (“Judah the Pious”), who came from the city of Siedlce (Shedlitz in Yiddish). He organized a group consisting of hundreds of Jews to walk from Poland to Jerusalem. The group marched throughout Jewish Poland wearing white burial shrouds, encouraging others to join them. Most of them died on the road. Yet, on October 17, 1700, the remnants arrived in Jerusalem.

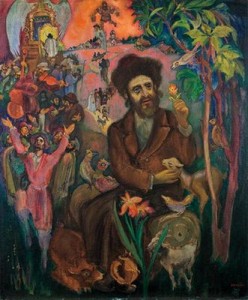

There are two distinct traditions regarding the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Hasidic Movement. The tradition of Chabad (Lubavitch) is that as an adolescent the Baal Shem Tov joined one of these bands of traveling holy men, eventually becoming the leader. That was the beginning of his career.

There is another tradition among Chassidim that claims he had nothing to do with such groups; he came into his own on his own. Indeed, he was opposed to them. We find later a letter of his to one of his colleagues and disciples, Jacob Joseph of Polonne, an ascetic who would go for long periods without eating, subject himself to physical privations such as rolling in the snow and wandering for months as a beggar. In the letter, the Baal Shem Tov writes very sharply that he should desist from such behavior. It was not only counter-productive as far as the Chassidic Movement was concerned, but for the person himself.

In today’s world there are still rabbis who make it their business to travel to remote Jewish communities and inspire the masses. In so doing, they are continuing an age-old Jewish tradition.