Beginning in the 1400s, the center of Jewish life shifted from Western Europe, Spain and the Mediterranean to Eastern Europe — especially Poland, Lithuania, White Russia and the Ukraine.

For the next 500 years, most of the creativity in Jewish life will take place in Eastern Europe, despite the fact that it will be a very inhospitable environment.

Most of the Jews lived in small towns in rural Europe. Living in a small town in US more often than not meant a loss of Judaism. Judaism is its strongest and has survived mainly in the urban centers. However, in Europe it was almost the reverse.

In the towns that had 20-40 families there was a strong, self-contained Jewish unit. There were even towns that did not have 10 adult males. The people from the town would travel to a larger town a number times a year to participate in communal prayers. All year they were without a quorum – yet remained intensely Jewish among the sea of non-Jews. That is a testament to the depth of their attachment to Judaism which they had.

To be a rabbi in one of these small towns was an honor. And each town had a rabbi. It also typically had a ritual slaughterer and others necessary for a Jewish-religious infrastructure. No one was paid much. There was a lot of hunger. A rabbi’s salary might be a few kopeks a week plus a goat. In many communities, the rabbi’s salary was that his wife was given the salt monopoly or the candle monopoly.

Rabbis would compete for these jobs even though the town barely had a Jewish population of any significance! Nevertheless, the vibrancy with which every Jew’s life revolved around Torah enabled that type of situation to exist in Eastern Europe.

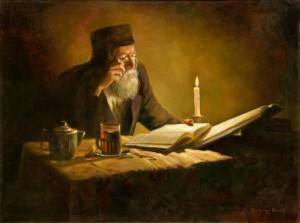

In Poland, the study and knowledge of Torah developed as it had not developed in centuries. Learning and scholarship were always part of Jewish life, but perhaps never more than in Eastern Europe, which is even more remarkable given the rampant illiteracy and ignorance of the non-Jewish culture.

Eastern European Jews had a concept of the yeshiva — a school or academy where Torah was taught — but it was not like we know it today. The main job of the rabbi was to learn most of the time and then teach others. The young men in the town who wanted to study would learn with him. If he found a young man with promise he would send him to a larger town to study with a greater rabbi. That was the educational system.

The more formal elementary school educational system in Poland was called the cheder (“room”). Jewish children went there from the age of three until bar mitzvah. There were no secular studies, and they stayed cheder all day. Consequently, in 10 years a child could gain a great deal of Torah knowledge.

Only the elite stayed after the age of bar mitzvah, because economically no one could afford it. During the average Jew’s life he would regularly come nightly to the synagogue, where classes were always held, and join different study groups.

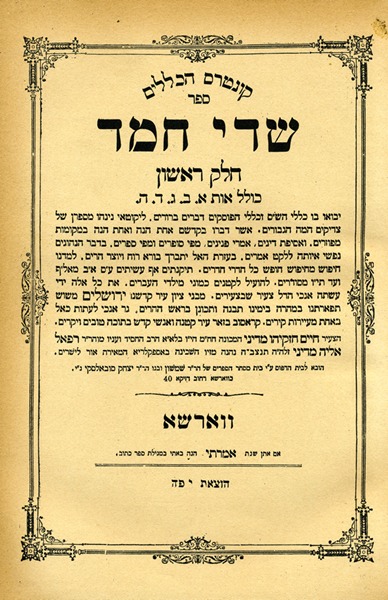

Their life revolved around the synagogue. There were also great Torah scholars who established advanced yeshivas throughout Lithuania, Poland and Russia. The famous rabbis of Poland were revered. Torah knowledge was how a Jew’s greatness was measured. There was no other form of study. If someone had a good mind, it was the only outlet for him. He could not go to Rutgers or Harvard. Because of that, the study of Torah reached a pinnacle. It was developed in Eastern Europe to a degree it had never been since the days of the sealing of the Babylonian Talmud.