In Jewish Lithuania and Russia during the 1800s there were various reactions to the coming of the Enlightenment/Haskalah. The Yeshiva Movement was one response. Another was the Mussar Movement, which had deep roots within the Jewish people and whose influence continues today.

In Jewish Lithuania and Russia during the 1800s there were various reactions to the coming of the Enlightenment/Haskalah. The Yeshiva Movement was one response. Another was the Mussar Movement, which had deep roots within the Jewish people and whose influence continues today.

Mussar means ethics or values. It was a movement to improve the Jewish people from within.

The founder of the movement and its greatest protagonist was one of the great men of Israel, Rabbi Yisroel Lipkin, better known as Rabbi Israel Salanter (1810–1883). Salant was a small Lithuanian-Russian village that produced three tremendous spiritual giants in one generation. The first was Rabbi Zundel of Salant, a disciple of the Gaon of Vilna. The second was Rabbi Samuel of Salant, who immigrated to Jerusalem while he was in his twenties and became chief rabbi of Jerusalem for the next 70 years (1838-1909).

The third is Rabbi Israel of Salant (or Rabbi Israel Salanter). Among his talents, he was a master of the epigram, the quick phrase that described the situation. One such epigram went: “Reform came to reform Judaism; I came to reform Jews.”

That capsulizes his Mussar Movement.

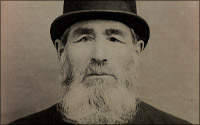

Rabbi Zundel of Salant

In the early 1820s, when Rabbi Salanter was yet a young man, he encountered Rabbi Zundel of Salant and was taken by his personality. Part of that personality was that he hid his piety, knowledge and greatness. He dressed and behaved outwardly like no one special and simply called himself “Zundel,” without any titles.

Many times Rabbi Zundel would go on solitary walks in the woods to meditate and pray. A young Israel Salanter – opinions vary if he was 11 or 14 – used to clandestinely follow “Zundel” on his forays into the woods in the hope of learning from and ultimately emulating his hidden, pious ways. The legend goes that one day Rabbi Zundel suddenly turned and caught him in the act of following him. He then told him, “If you want to be a great Jew, first you must be a God-fearing Jew.”

By that he meant to impress upon the young man the importance of emphasizing ethics over scholarship. There had always been a tremendous emphasis on Torah scholarship, and rightfully so. However, scholarship is not necessarily accompanied by the best of character traits, as the Talmud itself warned many times.

The words that Rabbi Zundel said landed deep in young Israel’s soul and made a profound impression. Later in life, Rabbi Israel Salanter said that when he was 14 he was able to say a complex Talmudic discourse (“pilpul”) the equal of anyone in the generation. Nevertheless, after this encounter with Rabbi Zundel he never did so again. Rabbi Zundel showed him that it was just the exhibition of a great mind, but was not true in the sense that it did not show the true greatness of a person.

Rabbi Israel resolved from that point on that he would not let himself be blinded from the truth by his own talents.

His Genius

Rabbi Israel Salanter was a genius of rare proportions. The stories about his intellectual prowess boggle the mind. One story is said to have occurred early in his attempt to establish the Mussar Movement. The best way to establish it was to first prove that he was an eminent Talmudic scholar, so he would travel from town to town and deliver discourses, saving only the last part to outline his feelings about mussar and ethics.

It once happened that a cynic tried to expose him as someone who did not possess any particularly special Torah scholarship. The custom was for the lecturer to post a long list of his topics and sources before delivering the class so others could prepare. A day before the lecture, they would post this list of perhaps 8-10 sources from places like the Talmud, Maimonides and Rashi.

This cynic secretly took down the source list that Rabbi Salanter had posted and replaced it with a completely different list of sources. Moreover, the sources on the list were completely unconnected; one had nothing to do with the other.

When Rabbi Salanter walked into the lecture hall five minutes beforehand he saw the replaced list and understood what had happened. Nevertheless, he delivered his lecture on those very sources in the most coherent and moving way. He found the underlying threads among topics which on the surface were completely disparate. It took rare genius to do it.

Another story demonstrates his greatness even further. Later in his life, when he was very old and living in Paris, he was asked to deliver a major discourse to a crowd numbering in the thousands. Suddenly, as he stood there in front of everyone he forgot what he was going to talk about. He put his head down and wept. After a few moments he lifted his head and said, “That was the best lecture. Look what happens to a human being. When I was 14, I could deliver a discourse as well as or better than anybody in Lithuania. Now I don’t know anything.” Then he descended from the pulpit and departed.

Eye witnesses said that it was so emotional that the entire audience was in tears. That was the greatest lesson in mussar.

Nevertheless, until the end he was the shining star, so to speak, in a constellation of great men.

Reforming Jews, Not Judaism

Jewish culture in the 1800s in Russia suffered from certain chronic problems, which the Haskalah took advantage of, as we discussed before. The moral and social defects in Russian Jewish society were used by the Haskalah to attack traditional Jewry, as though it was the Torah’s fault. Of course, one should never confuse Jews with Judaism. If an otherwise fine and upstanding Jew does something wrong it is not Judaism’s fault. Nevertheless, on a mass scale the Haskalah mounted its attack on Judaism based on the societal character faults.

Rabbi Israel Salanter made it his personal mission to turn that around.

His method was to establish what he called “Houses of Mussar,” i.e. houses in the community devoted to people who would come on a regular basis to study the works of Jewish ethics. Through this study, and the encounter with people whole-heartedly committed to ethics, the level of ethical behavior among the masses would be raised.

By ethical behavior he did not only mean behavior between people, but also toward God. That included how to keep a commandment correctly, how to make a blessing correctly, how to dress, speak and behave correctly.

Rabbi Salanter was able to pull it off because he himself was such an outstanding, exemplary person.

Houses of Mussar

Rabbi Salanter envisioned spreading his movement through Houses of Mussar, as we said. He began these efforts in Vilna and his movement quickly became very popular. He intended it to be a movement not just for scholars, but a mass movement including laymen — and that is how it began. He had hundreds and hundreds of merchant-class businessmen as well as lower-class laborers participating in the study of mussar, committing themselves to a higher standard of ethical behavior. He was so successful that it was recognizable in town that something had changed; that something radical was going on.

Even though Vilna was the seat of Torah scholarship in Lithuania it was also the center of Haskalah. As Rabbi Salanter’s successes with his Mussar Movement mounted in Vilna the Maskilim (followers of Haskalah) felt more and more threatened.

In truth, the leading Maskilim badly misjudged Rabbi Salanter. They didn’t understand his distinction between reforming Jews vs. reforming Judaism. Somehow they came to the mistaken notion that he would support Haskalah and that his campaign to change the Jewish people made him an ally.

This led to moment of truth. In 1848, the Russian government established a rabbinical seminary in Vilna under the auspices of the Russian Ministry of Education. They appointed Maskilim and even non-Jews as members of the faculty. Then they proposed that Rabbi Israel Salanter become the head of the institution.

At first he refused the Maskilim. Then they had the Russian government ask him, knowing that it was an invitation one could not refuse. The Russians had a penchant for sending those who refused their “generosity” away to Siberia. Therefore, Rabbi Salanter left Vilna in the dead of night, never to return again.

Mussar in Kovno

He moved farther north into Lithuania, to the city of Kovno (Kaunas), the capital. There he began again his Mussar Movement. However, in Kovno the movement took a far different form.

In Vilna it was a mass movement, one that reached all sectors of the population. It did not have strong opposition. It was viewed as constructive and positive, combatting the ravages that were occurring in Jewish life.

In Kovno, the Mussar Movement became an elitist movement. It did not reach much of the middle class; it certainly did not reach the lower class. Most of all, in Kovno it had very strong opposition – first and foremost from the Maskilim, who were tipped off by the Maskilim in Vilna.

To them, Rabbi Salanter and his movement and represented the greatest threat to their movement, especially its emphasis on behavior and even dress. A great deal of their success was due to a public stream of accusations that traditional Jews were unkept, unclean and uncouth. Rabbi Salanter’s Mussar Movement not only emphasized ethical behavior but a certain degree of outward deportment that took away some of the Maskilim’s favorite tactics for winning adherents. They saw the changes Rabbi Salanter brought about as unwelcome changes and became sworn enemies of the movement.

Departing West

Having started the ball rolling establishing mussar in Eastern Europe, Rabbi Salanter left to attempt to accomplish a much more daunting task: spreading it to Western Europe.

His main disciple quotes him as once saying that his reason for departing was the following parable: When the brakes on a locomotive have failed and the train hurtling down the hill out of control there is no force in the world that can stop it. But once the train has come to a stop at the bottom of the hill, and the inertia has dissipated, one can fix the brakes and repair whatever needs to be repaired.

Lithuania and Eastern European Jewry, Rabbi Salanter explained, is still the train hurtling down the hill; there is no way to fully stop it. All efforts will prove to be futile. However, Western European Jewry (which fell down the hill 100 years earlier) is at the bottom already, so there is a chance to be of influence and change things.

He therefore left Lithuania to travel throughout Germany and France, ultimately settling in Paris, attempting to strengthen the Jewish people wherever he went. The pressures of assimilation were great in Western Europe. Jews – those at least who still identified themselves as Jews — often lived as refugees in the slums of the great cities trying to hang onto whatever Judaism they had. Rabbi Salanter targeted them for his efforts.

The Mussar Movement was the complement – the necessary missing piece – that combined with the Yeshiva Movement to combat the ravages of assimilation and lighten the terrible burden of poverty and persecution that Jews suffered in Europe. It gave them that added spiritual dimension, transformed their lives into something above the mundane and created great people that would be role models for others. Their example still lives among us today.