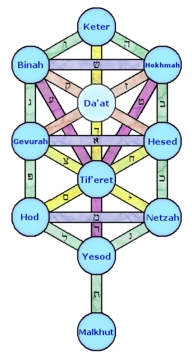

Let me say at the outset that I am not a scholar of Kabbala, the mystical tradition of Judaism. I don’t understand it myself, let alone can I explain it to others. But what I can attempt to explain are the historical forces that gave rise to its explosive influence in the 16th century. Without an understanding of this, it is difficult to understand the motives and dynamics of Jewish history in successive centuries, including our own.

I also want to say that in our time, Kabbala has been cheapened. If Madonna is a Kabbalist, then I’m an astronaut. What passes as Kabbala in popular culture has nothing to do with real Kabbala.

As rational and understandable as the tenets of Judaism are, ultimate understanding of it lies beyond the realm of the intellect. Therefore, there was always a strain of mysticism within Judaism, but for centuries, its study went on amongst a few select scholars in an unobtrusive, almost invisible fashion. This anonymity ceased in the 16th century. Then, the ideas of Kabbala became not only well-known, but dominant in Jewish thought, and they continue to be today.

After the calamities of the Middle Ages, particularly the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Jewish scholars began to re-examine the meaning of exile. The very concept underwent an evolution. Originally, exile was seen purely and starkly as a punishment for sins. The Books of the Prophets explain it that way – it’s like a prison sentence. The guilty person serves his time, and when it’s over, he goes home.

That argument is easy to maintain for a short exile, like the first Babylonian exile, which lasted seventy years. But in the Middle Ages, that explanation was no longer sufficient. What sin of the Jewish people was so great that it required such a long, bloody, and painful exile? The Jews may have sinned, but if we compare the Jews’ behavior to many other nations and religious groups in history, it is difficult to place us at the bottom of the ladder. We are not found to be that wanting morally or spiritually. The punishment seems disproportionate to the sin.

This sums up the core problem of Jewish history. Why are we so persecuted? What spiritual purpose does it serve? If the exile lasts another hundred years, will we become better? Are we a better people now after Hitler? I think all of us in hindsight would say that the world was better off a hundred years ago than it is today. It was closer to redemption then. So what is the purpose of this exile? Who needs it?

Lest I sound too blasphemous, I am merely raising the issue that has gnawed at Jewish thought for the last 500 years. It’s not such a problem to us since we live in relative comfort and serenity, even if it’s false serenity. The experience of the exile, certainly in America, is pleasant. But to Jews who had been driven from their homes in the Spanish Inquisition and Expulsion, to Jews who had experienced the pogroms of the Black Death, it was a real problem.

The popularity of Kabbala lay in the fact that it gave answers to these problems. It attempted to make sense out of a world that is completely illogical. But just as all the terrible questions regarding the Holocaust have no simple answers, the Kabbalistic answers are not simple. Anyone who attempts to give them simple does a great disservice to the Jewish people and to Judaism itself.