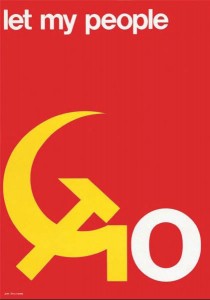

In the 1970s, for the first time Jews in the Soviet Union were allowed to leave – at first a small trickle and then a strong stream. Until then, it was inconceivable that the last few remaining Jews in the Soviet Union, who cared to identify themselves as Jews, would ever escape the prison of the Communist Utopia.

In the 1970s, for the first time Jews in the Soviet Union were allowed to leave – at first a small trickle and then a strong stream. Until then, it was inconceivable that the last few remaining Jews in the Soviet Union, who cared to identify themselves as Jews, would ever escape the prison of the Communist Utopia.

One has to remember that in the days of Stalin and Khrushchev Soviet Russia was a sealed fortress. People did not leave. One also has to remember that, by that time, the Soviet Union had been under communist rule for half a century. There had been no organized Jewish life. There had not even been a Jewish calendar published. There were no rabbis or Jewish education. Yet, somehow the spark of Judaism, and the spark of being Jewish, remained alive.

The spark of Judaism was preserved by underground groups, such as Chabad, along with the help of outsiders, such as Western Jews, who visited at great personal risk, discomfort and cost. Some came to teach in secret groups. All tried to bring with them prayer books, study books, and needed ritual items to help revitalize Jewish life in the Soviet Union. They were trained what to say to the KGB agents. They also needed to know what to say to the customs inspectors that went through their suitcases with a fine tooth comb.

Although generally a frightening experience, sometimes such encounters had humor, even hilarity, attached thereto. For instance one British “tourist” tried to bring in a chalaf – a very large, sharp knife used by ritual slaughterers to kill animals in accordance with kashrut laws. The customs inspector, looking shocked, asked the “tourist” – “What is this for? This big knife?”

The “tourist,” with the aplomb that only an Englishman can muster in a very ticklish situation, answered by taking out a salami that was also in the suitcase and sweetly replying: “Well, I have to cut my salami with something!” The knife made it through the customs inspector.

Another example: An extremely ingenious traveler took special black ink, used exclusively for safrut – the writing of the script in a sefer torah, tefilin and mezuzot – in a Coke bottle in his hand luggage. Unexpectedly the customs official in Moscow confiscated this bottle as a symbol of Western decadence attempting to contaminate the Soviet Union. At first, the traveler was in a state of great exasperation, but then his mood changed, almost hilarious at the idea of the official guzzling the contents of that bottle.

Through untold numerous acts of selfless devotion, there was a significant revival of Jewish life in the Soviet Union. People began to study Torah and observe the traditions – at the risk of everything. Eventually it was the movement of the Jewish refuseniks and the pressure to allow Soviet Jewry to leave Russia that helped cause the “evil empire” to crumble.

And that Jewish basis which on the surface appears to be purely nationalistic is really an expression of Jewish faith and religious belief, for all Jewish nationalism is rooted in the ideas of Torah and Jewish tradition. The fact that the decades of anti-Jewish and anti-religious repression were not able to snuff that spark is itself a testament to the eternal quality of the Jewish people – not to mention the momentous times in which we live. Few would have imagined a decade earlier that such a thing could have occurred.