Years ago, I visited the northern village of Rosh Pina, and because its story represents in a microcosm the story of the Jewish settlement in the land of Israel, I want to focus on it now.

In 1878, a group of eighteen young and idealistic yeshiva students from Safed left their home city and decided to find an agricultural settlement where they would earn their livelihood by tilling the soil part of the day and studying the rest. They had no practical experience in farming, but they were willing to learn and felt that enthusiasm would overcome all obstacles. With the meager financial resources that they possessed, they purchased land from the local Arabs near the village of Ja’ouneh. They named their little farming settlement Gai Oni (literally, “the valley of my strength”) because of its similar sound to Ja’ouneh.

The young men were really raw to farming. They planted potatoes and were crushed when the expected crop did not appear on the surface of their fields. Disappointed, they turned over the soil in order to plant a new crop and discovered their precious potatoes growing in the ground! But in spite of this early success, they could not make a go of their venture, and faced with disease and hunger, they disbanded three years later. Most returned to Safed, but two or three remained, hoping for a miracle that would allow them to continue with the development of the farming settlement.

At around this time, the movement called “the Lovers of Zion,” was founded. Predating Herzl’s movement, its sole aim was to support Jewish immigration to the land of Israel. Unlike Herzl’s movement, it had no aspirations for a Jewish state. In 1882, some members of this group arrived at Gai Oni and decided to settle there. They renamed the village “Rosh Pina,” which means “the top cornerstone.” The name was taken from the verse in Psalms that reads: “The stone that the builders had rejected has now become the top cornerstone.”

The realities of Rosh Pina were no less difficult and painful than they were for Gai Oni. By 1883, the settlement was once again faced with ruin and abandonment.

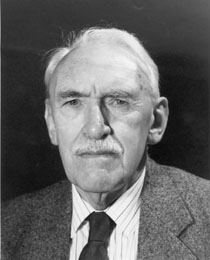

Then appeared on the scene one of the wondrous personalities of Jewish life: Baron Edmond de Rothschild. He adopted the settlement and extended to it his patronage and wealth. But there are no free lunches, and together with the Baron’s largesse came his administrators, mainly French Jews who looked down with scorn on their Eastern European brethren. The numerous complaints Baron Rothschild received from the residents about the behavior of his administrators brought only sporadic relief to the tense situation.

In spite of this, the community prospered. By 1900, the settlement numbered over 500. It included an administration building, a school, a synagogue, and other public buildings. The agricultural effort was now deflected from potatoes to tobacco and mulberry trees (for the cultivation of silkworms that would produce silk). A winery, the Baron’s favorite agricultural industry, was also constructed, and soon wine bottling and sales began.

And so, by the first decade of the 20th century, Rosh Pina became the center of Jewish settlement in the Galilee.