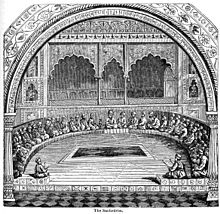

When the Jews were driven from Spain in 1492 the effect on Jewish morale was so devastating that many rabbis looked for a method by which the Jewish people could be strengthened. It was not in the hands of the Jewish people to improve their material lot, so the rabbis concentrated on how the Jewish people could be strengthened spiritually. One of the ideas floated then that the time was now propitious for the reestablishment of the Sanhedrin, the Great Court of Judaism originating in biblical times that existed until the 5th century of the Common Era. This court decided all matters of Jewish law, set the calendar and was the central body of authority of Jewish life.

The reasons this seemed like a propitious time was because a) it would give a boost to the collective Jewish ego and b) for the first time in almost 1,000 years a sizable Jewish settlement existed in the Land of Israel, including leading Jewish scholars of great note. Consequently, one great scholar named Rabbi Jacob Beirav (also spelled Yakov Berav, Berab or Bei Rav) felt it was the right time to reformulate the Sanhedrin. However, his first hurdle was Jewish law.

A member of the Sanhedrin required a special level of ordination (semichah) and the only way to obtain it was to be given it by someone who himself had been so ordained. In other words, the first conferring of this ordination was Moses to the 70 elders who constituted the first Sanhedrin, as recounted in the Bible. Then they had the right to ordain their students and so on throughout the generations.

The Sanhedrin was disbanded in the 5th century due primarily to severe persecution at the hands of the nascent Christians. Those who had the ordination were not able to pass it on any longer. Once it died with them there was no way of apparently ever restoring it. Because of that, Jewish tradition and the Jewish masses believed that the Sanhedrin would only be restored at the time of the Messianic Era.

Nevertheless, Maimonides – based on a tradition he had in his family and from his teachers – believed that the Sanhedrin will not necessarily be renewed miraculously by the Messiah. He wrote that if the sages of Israel who lived in the Land of Israel will gather together and choose one among them as worthy of ordination then he would be considered to have been ordained with the original ordination. He, in turn, could ordain 69 or 70 men until the entire Sanhedrin was reconstituted.

That is what happened in the 1500s, almost four centuries after Maimonides. There never was such a bold attempt to change the course of Jewish history and life. Rabbi Jacob Beirav, who was recognized as the leading authority of his time, was the mentor of Rabbi Joseph Caro. He called a convocation in the Land of Israel of the great scholars regarding this matter. They voted unanimously to entrust the ordination to Rabbi Jacob Beirav, who now in effect had the ordination necessary to ordinate other worthy scholars as members of the reconstituted Sanhedrin.

In order to do so, he sent letters of ordination to other great scholars of the time living in the Land of Israel. One of those was Rabbi Joseph Caro. Another was Rabbi Moses Alshich, the famous preacher in Safed. Yet another letter he sent out was to the chief rabbi of Jerusalem, Rabbi Levi ibn Habib, who not only refused to accept the ordination for himself but opposed the entire idea. He said that he was not certain that Maimonides was correct, and even if he was, now was not the right time and the pool of candidates were not the right people.

This opened a very bitter and protracted dispute. Most of the great rabbis outside of Israel opposed it. Rabbi Jacob Beirav said it made no difference what rabbis outside of Israel thought, because they had no voice in the matter. Maimonides only required those living inside the Land of Israel, and since the majority of those were in favor of it he was willing to defend what he had done.

Nevertheless, the Sanhedrin can only have authority if the people are willing to accept what it says. The Jewish people did not possess an army or police force, or any means of enforcing any decision. If the public was not willing to grant the decision-makers the authority to establish the law, then in effect any chance for acceptance of the idea was nullified. That is what happened. Rabbi Levi Habib was too formidable a scholar, and his opposition too vociferous. Instead of becoming a positive, unifying force, the attempt to reinstate the Great Sanhedrin became terribly divisive.

From some of his writings, it seems clear that Rabbi Joseph Caro considered the ordination valid. However, it is equally clear that he was not willing to wage what would have been enormously divisive battle to have it enforced. Consequently, this special ordination was not passed on; it ended with those who were granted it by Rabbi Jacob Beirav. The great project to reinstate the original ordination died.