In this post, I would like to discuss Rashi, the greatest of commentators to the Torah and Talmud. “Rashi” is an acronym for the name Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, but Jewish tradition tells us it also stands for “rebbe shel Yisrael,” which means, “the teacher of the Jewish people.”

Rashi occupies a unique place in the Jewish world, on par with Moses. The sages who wrote the Mishnah and Talmud and even the Rambam were not the teachers of the entire Jewish people. They were the teachers of scholars, of those who were able to appreciate them.

Rashi is our kindergarten teacher. When little children learn his commentary on the Bible for the first time, it makes perfect sense to them. Then, as we graduate to Talmud, Rashi takes us by the hand and leads us through that vast sea of unpunctuated words, telling us, “The sentence ends here. This is what it means. This is the question. This is the answer.” So as we grow older and hopefully wiser, we realize that Rashi was not only our kindergarten teacher, Rashi signed our PhD.

But Rashi’s commentary is not just intellectual. His love of humanity shines through. There’s not one denigrating word in his entire commentary, which is an extraordinary accomplishment. Some teachers will wipe the floor with you. I’ve had a few. But effective teachers don’t holler. “Words of the wise men are heard when spoken softly.” (Ecclesiastes 9:7) That’s Rashi. He’s soft-spoken. He’s gentle. He’s your friend.

Rashi began his magnum opus, his commentary to the Talmud, when he was a young man at the yeshiva in Mainz. The printing press had not been invented yet, so there were only a few copies of the Talmud available. Rashi’s correspondence mentions approximately one copy for every 25 students. So they studied by keeping notebooks on the lectures and sharing with each other. These notebooks then became even more important than the text because they explained what the text meant.

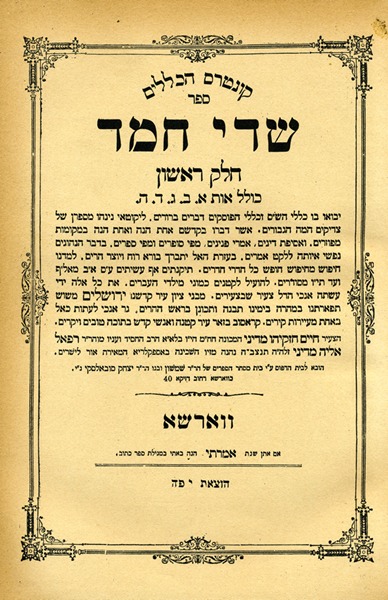

By the time Rashi entered the yeshiva in Mainz, it had existed for 65 years. Over those years, a general notebook had been composed – the work of three generations of students, called the Kuntres Mainz. But whereas many of the other students adopted the notebook whole, Rashi sought to improve it. From his youth until his last day, he kept rewriting, erasing, and adding words to it. That perfectionism is the mark of supreme intellectual honesty.

Much of Rashi’s commentary was not written in his own hand but by his daughters. He dictated, and they wrote down what he said. This explains, in part, his prodigious output. There are legends that his daughters sometimes corrected him. But whether true or not, it is without question that he raised his daughters as scholars in an age when most women were illiterate, and they helped promulgate his great commentary.

Rashi’s grandson Rabbeinu Tam said, “I could have written my grandfather’s commentary to the Talmud, but his commentary to the Bible is something unique.” Rashi made the Bible accessible to everybody – from the smallest child to the greatest scholar. How did he do it? As he tells us over and over again, “I am only coming to tell you the simple meaning of the text.” Rashi was not a philosopher. He just explained the meaning of each and every word, and from there, you can piece together the overall picture on your own level.

Rashi’s commentary is also interspersed with Talmudic legends, which are our bridge to Biblical times. With all due respect to archaeologists and their attempt to open a window to life back then, they may uncover genuine artifacts, but they haven’t got a clue as to what the Jewish people were like. A Jew does not feel a connection to King David by seeing his sword in the Israel Museum. A Jew connects to King David through the stories of the Bible, and those stories come to life through the Talmudic stories cited by Rashi.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Jewish people could not have made it through the exile without Torah. Torah gives us a connection to God, an understanding of where we come from, and why we’re here now. But without Rashi, the Torah would have been forgotten. And perhaps most amazingly of all, he lived during the First Crusade when the exile turned really bloody, yet he writes as though he’s sitting in the middle of paradise without a worry in the world except the simple meaning of the text.

That’s greatness. That’s our teacher. And that is how he preserved the Jewish people.

For more about the life of Rashi, please check out our film, Rashi: A Light After the Dark Ages.