Today is the minor holiday of Lag B’Omer, a break in the semi-mourning period after Passover, and the anniversary of the passing of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. This great sage was the primary disciple of Rabbi Akiva, who inherited from his great mentor a strong antipathy towards Roman rule and culture.

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his teacher Rabbi Akiva lived in one of the most turbulent periods in Jewish history. The Roman emperor Hadrian was in power, and though he had originally treated the Jews fairly, he underwent a radical change in the middle of his reign. At first, he had been involved in other wars, and didn’t want trouble with the Jews, who had fought so fiercely in 66-70 CE (though they ultimately lost). He was open to the idea of allowing the Jews rebuild their Temple, as long as they would remain under Roman rule. But five years later, he decreed that not only shouldn’t the Temple be rebuilt, the ruins should be razed so that the Jews would have no hope of trying.

This was brought about the popular revolt led by Bar Kochba, who was a tremendous warrior and organizer. But once he was victorious and in a position of leadership, Bar Kochba turned paranoid. By definition, a leader is in the public view, and everybody can take shots him, which they always do. So Bar Kochba “lost it.” His paranoia was so extreme that he killed his own uncle. Upon seeing this brutality, Rabbi Akiva withdrew his original support of Bar Kochba.

After Bar Kochba’s defeat, Hadrian began to persecute the rabbis unmercifully. He realized where the leadership really lay, and he figured the only way to make the Jews docile was to get rid of the rabbis. Thus, Rabbi Akiva, along with nine other great sages, was tortured to death.

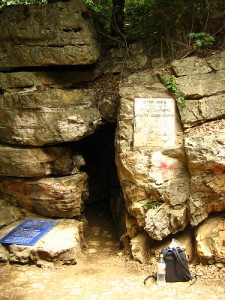

But rabbis are hard to get rid of. The Romans may have killed Rabbi Akiva, but his disciple Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai rose up in his place. And Rabbi Shimon was neither reticent nor politically correct. Some of his contemporaries openly praised the Romans for rebuilding the physical infrastructure of the land. They felt the Jews should compromise with them. Rabbi Shimon, however, was outspoken in his condemnation, stating that even the Romans’ seemingly positive actions stemmed from sinister motives. Then, a Jewish spy working for the Roman government reported Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s words to the Roman authorities, and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Rabbi Shimon, together with his son Elazar, fled to the desert and found refuge in a cave where they spent thirteen years in hiding.

During that long and isolated sojourn in the desert cave, Rabbi Shimon was able to delve into the hidden, mystical level of Torah and comment and explain its mysteries. It was at this time that he wrote The Zohar, the essential book of Kabbalah, though the book was not published until the fourteenth century by a Spanish Jew, Moses de Leon. Though there was much debate over the authenticity of the book, tradition holds fast that it was Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai’s. The Zohar has such depth and spirituality, the majority opinion is that it was beyond the ability of Moses de Leon to write himself.

After thirteen years in the cave, there was a regime change in Rome, and Shimon bar Yochai and his son were granted amnesty. This marks the beginning of the melting of the ice in Roman relations with the Jews, which would reach its height with Rabbi Judah the Prince, who would develop a friendship with Emperor Antoninus Pius. That friendship is what allowed the oral tradition of Judaism, the Mishnah, to be written.

When Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai emerged from their cave and returned to the society of the land of Israel, he had achieved such a level of spirituality that he could not countenance the ordinary workday activities of his fellow Jews who did not spend every waking moment in the study of Torah. Clearly, he was someone who brooked no compromises.

Tradition ascribes the minor holiday of Lag B’Omer as the anniversary of the death of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. He is buried on Mount Meron in the Upper Galilee, and up to 500,000 Jews visit the site each year on this day. Large bonfires are lit, young boys are given their first haircut, and entire families encamp on Mount Meron in commemoration of the day. The custom of bonfires has spread from Mount Meron throughout the rest of the Jewish world, inside Israel and out, though there is much rabbinic opinion that disapproves of this custom. Nevertheless, it is apparently here to stay, acrid smoke and dangerous sparks notwithstanding.

The combination of Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai’s fierce opposition to Roman ways, his superhuman devotion to Torah study, and his contributions to the rebuilding of Jewish life after the Hadrianic persecutions, all combine to make him one of the giants of Jewish history and tradition.