Whereas younger people in their adolescent and early adulthood years constantly look forward (I think that is why history teachers find it so difficult to interest them in the subject at hand) we older folks are much more prone to look back and restudy past events that were meaningful to us. The advantage of age and life experience allows a perspective on life that the younger generation has not as yet gained.

Those of us who lived through the last two-thirds of the twentieth century experienced one of the most turbulent and certainly the most violent and murderous period in human history. Between Hitler, Stalin, Mao and an assortment of lesser murderers, over one hundred fifty million people lost their lives by governmental action, war and terror. This represents a greater number than the entire estimated population of the then known world at the time of Julius Caesar. To this astronomical number needs to be added another forty million people who died in World War I and in the influenza epidemic that swept the world in its aftermath. There had never before in human history occurred such a bloodletting over a condensed period of less than a hundred years.

The twentieth century also recorded the destruction of the old order that prevailed in Europe and the Middle East for many centuries. The four great empires of Europe – the Ottoman, German, Austrian and Russian – were destroyed in World War I. The surviving empires – the British, French and the minor colonial powers – were greatly weakened by that great war even though at the time they failed to truly realize that their days as imperial powers were now coming to an end. But the generation of World War I is almost gone from the scene and all of its horrors are now relegated to the pages of books and to grainy films.

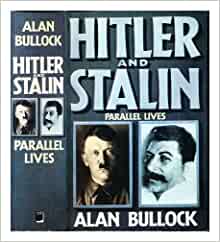

It is the generation of World War II that is now also beginning to pass from the scene as well. This realization makes me more likely than ever to look back at that watershed of human history and its aftermath, much of which still influences all of humanity today. How could such a disaster have occurred? Who was responsible for it? Was it inevitable or was it caused solely by evil individuals? And of course hovering over all of this is the specter of the Holocaust and its disastrous effects upon world Jewry. I therefore, in my dotage and in a looking back mode, purchased a book by Allan Bullock, the British historian, entitled “Hitler and Stalin, Two Parallel Lives” and read all one thousand pages of it avidly. Bullock’s talent is to interweave the lives of these two monsters together and show how they almost by themselves created the disaster that was Europe for a large part of the twentieth century. It is a masterpiece of detail and research and so easily readable that it turns into a page turner. Its ability to explain the madness of each of the protagonists, to make sense of the inexplicable and almost indescribable decisions and policies of these two men and to describe the power that each of them had over entire nations of millions of people is truly enviable.

Bullock enters the warped minds of each of his subjects, Hitler and Stalin, and shows how their behavior and policies, self-destructive and insane as they may have been, made perfect sense to them from their own perspective. It is chilling reading but it certainly puts the century into some sort of perspective and emphasizes to the reader how history is made by people and their policies and beliefs and not by blind historical forces of economies, social systems or class struggles. The Jewish view of life is that all individuals are responsible for their actions and decisions and the consequences that flow from them. Hitler and Stalin, and later Mao and Pol Pot and others of this ilk, are responsible personally for all of the tens and tens of millions done to death through their decisions in the twentieth century. As being a member of the generation that witnessed these events, I remember vividly the impressions they made upon me.

As a small child I remember my parents listening in dismay to the screeching hysterical speeches broadcast and translated over American radio of Adolf Hitler. The voice of that evil person is deeply embedded in my memory. I remember the sight of the first Holocaust survivors reaching Chicago in 1947. My mother and father gave away our dining room table and chairs to one of the survivor families who had nothing. We ate in our kitchen for a number of years thereafter and never felt the poorer thereby. I never thought my parents’ behavior in this matter strange or even especially magnanimous. It was natural to me having grown up with my grandfather and my parents and watching their daily behavior and acts of hospitality, charity and kindness towards others.

At that time the Irgun and Lechi were fighting the British and the Arabs in the Land of Israel. The only newspaper that regularly carried news about the situation then in Palestine was the New York Times, which obviously did not yet appear in Chicago at that time on a regular basis. About once every two weeks a copy of the paper miraculously appeared in our school and everyone waited in line to read the old news. It was heroic for us to feel that Jews were actually fighting others for their rights and land. The Friday that the state was declared, May 14, 1948, I walked to the synagogue with my father as was our customary behavior. I remember that he wept every step of the way. It was at that moment that the idea of my living in Jerusalem in a Jewish state crystallized in my mind and heart. It took almost fifty years for it to be realized, with a great many twists and turns along the way, but somehow the Lord allowed it to truly happen. My gratitude for that knows no bounds. The enthusiasm in the Jewish world, in all of its sections and circles, was then overwhelming. At a mass rally that was held at the Chicago Stadium to mark the occasion of the creation of the state, the blue and white flag of Israel was raised to the rafters. Uncontrollable weeping swept over the nearly twenty thousand people crammed into the stadium. The entire two thousand year- long exile with all of its tragedies poured out of the Jewish souls gathered there. It was an electric moment. I regret deeply that my children and grandchildren do not have such a moment to remember when their time will come to look back.

Though not yet of army draft age, I remember my trepidation at the announcement of the invasion of South Korea by North Korean troops and the subsequent American response. Stalin was still somewhat of a revered figure in America, especially in liberal Jewish America. His true nature and the real face of Soviet Communist life had not yet been fully revealed. I attended college at a university infested with left leaning fellow-travelers to whom the Soviet Union could do no wrong and the United States could do no right. However, my teachers at the yeshiva, some of whom had tasted the paradise of Soviet life during the Russian army’s occupation of Lithuania in 1940 and 1941, set us then naïve Americans straight about atheistic Communism and the benevolence of the great “Father of Mankind,” Josef Stalin.

Reading Bullock’s book only served to confirm to me a fact that I have long known in my life experience – how right my rabbis were and how wooly-headed and wrong most of my college professors were. And this rule applies not only in relation to attitudes and judgments towards Stalin and the Soviet Union. It has proven itself true regarding almost all other matters of life and the world itself. The opinions of Torah scholars on all matters of life should never be discounted or shrugged off lightly. They are the pegs upon which the tent of our lives holds firm. Looking back should not be a matter of nostalgia solely. Nostalgia often distorts reality, both past and present. The past is a masterful teacher if we only let it penetrate our minds and hearts and learn from it. And only if we have an accurate and mostly true assessment of what that past actually contained and was. The past can never be reconstructed to operate in the present. But making intelligent decisions, personal and national in the present, requires a knowledge and appreciation of the past. Looking back is an essential part of wisdom and probity in life. Every generation is individual, special and unique. But it must be admitted that those of us who lived through the last two-thirds of the twentieth century certainly lived through an unequalled epic time in human and Jewish history.