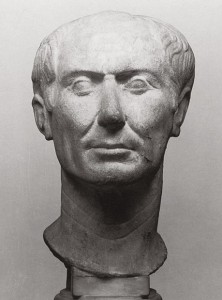

On January 10, 49 BCE, Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon, signaling the start of civil war between his forces and those of the Roman who defiled the Holy of Holies.

Pompey was a talented, ruthless general for Rome. He was the first Roman leader to understand that Rome could not successfully control the Middle East if it did not control Judea. Even if Judea was merely a neutral independent it would serve as a wedge between the Northern Empire (Syria) and the Southern Empire (Egypt). Therefore, he looked for a way to get himself in power in Judea.

Ideally, he did not want to do it through war, because the Jews – the Hasmoneans/Maccabees – had a fearsome reputation. The Romans referred to the Jews as “porcupines.” Just as a porcupine is an animal that even great predators avoid, so too the Jews. Even if you ate it you would be sorry. The Jews had the reputation as difficult to fight in a war and impossible to govern. Moreover, the Romans viewed the Jews as “atheists” or “non-believers.” Anyone who was religious, in their world view, had a god that you could see. They could not comprehend an invisible God with a Temple that had no visible idol to worship.

Therefore, Pompey was not interested in going to war with the Jews or running their country. However, he did want to control them somehow.

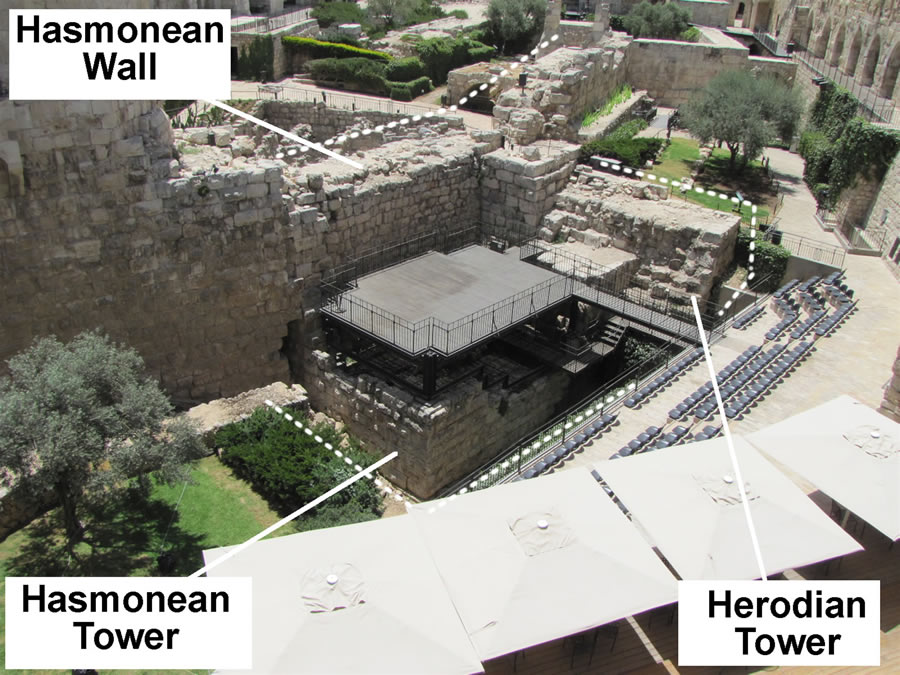

In the year 64 BCE, Pompey appeared in Damascus. Warring factions of Jews sent representatives to convince the Roman to side with them and not their opponent. (The Sanhedrin, ever wary of allowing Rome in the door – and history would prove their caution warranted — sent a delegation saying that Rome’s intervention wasn’t needed.) Pompey listened and then took his time responding. In 63 BCE, he arrived in Jerusalem. The Jewish forces lead by Hyrcanus promptly withdrew. The forces of his opponent, Aristobulus, fought against Pompey and Hyrcanus. After two months, the Romans broke through and massacred some 12,000 of the Jews defending the Temple.

According to Josephus, Pompey stepped into the Holy of Holies, the innermost sanctum of the Temple. However, he did not take any booty or interrupt the services of the Temple. The next day he withdrew him army from the Temple Mount and returned it to the authority of the Jews.

Nevertheless, for all practical purposes, Judea was now under Roman domination.

His work done in Jerusalem, Pompey returned to Rome expecting to be made the Emperor. However, he had strong competition for the job. One of his competitors was Julius Caesar, who was a great general in his own right. He did in the West what Pompey had done in the East and subdued the peoples in what is today England, France and the Rhineland of Germany.

These two great Roman generals agreed that Rome would be run by a Triumvirate: Julius Caesar, Pompey and a third General, Crassus. However, the Triumvirate lasted only five years, leaving Pompey and Caesar jockeying for control.

The Senate of Rome backed Pompey, but Caesar boldly marched his army across the Rubicon, the famous river that marked the boundary between Italy proper to the south and its provinces to the north. Roman law forbade a Roman army to cross the river. In doing so, Caesar was committing an act of war. (That is why the popular idiom, “Crossing the Rubicon” means to pass a point of no return.)

As Caesar’s army entered Rome, Pompey and the Roman Senate fled for their lives. Caesar declared himself Emperor and pursued Pompey all the way to Egypt. Once there, he committed a rare tactical blunder and found himself besieged in Alexandria by Pompey’s army and its allies. Sorely in need of friends, he looked for any help that would extricate him from his dangerous situation.

Until that time, Hyrcanus had been an official ally of Pompey. However, he shrewdly switched sides and declared his allegiance to Caesar. He then committed over 3,000 Jewish soldiers to an expeditionary force that invaded Egypt and helped raise the siege of Alexandria.

Thus, when the Roman civil war ended in Julius Caesar’s complete victory Hyrcanus was in a fortuitous position. Indeed, Caesar showed the Jews his gratitude for their help. He revoked the harsh decrees and burdensome taxation imposed by Pompey. He also allowed the walls and fortifications of Jerusalem to be rebuilt and restored Jaffa as well as a number of other coastal cities to Jewish rule.

When Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE, it was a cataclysmic event in the Roman Empire… and also worried the Jews: Would his successor be as positively disposed toward them? Tragically, that eventual successor, Marc Antony, gave power to a man whose rule was as antithetical to Jewish principles and ideals as imaginable. That man was Herod, a murderous, tyrant whose ways would eventually lead to the destruction of the Jewish commonwealth and the beginning of the long exile that Jews still find themselves in.