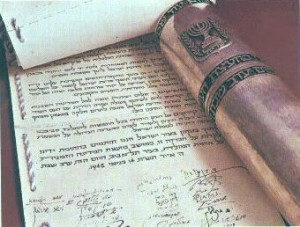

The religious-secular divide in the modern State of Israel is perhaps nowhere more poignantly illustrated than in the wrangling that went on to word its Declaration of Independence.

The group assigned to author it included everyone from extreme communists to the very religiously pious, including Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin, head of the Agudath Israel and brother-in-law of the Gerrer Rebbe. How would they produce a document that everyone would agree to? If it stated too much or too little, or stated anything too forcefully, there would be dissenters.

Each side made compromises by watering down the document to the point that it was almost meaningless. There were no Thomas Jefferson’s here. Nevertheless, at least they were coming to agreements – until they reached the question whether or not to mention the name of God.

The religious Jews asked how it was possible to have a declaration of the Jewish state without mentioning the name of God? The communists, socialists and atheists, on the other hand, said they had been fighting for a century to get rid of this medieval oppression and clericalism.

If nothing else, Ben Gurion was a very pragmatic person. He formed a committee of four to negotiate the matter. They came up with an ambiguous phrase: “With faith in the Rock of Israel.” Many atheists wanted to take out “Rock of Israel” completely. Others thought it was acceptable, however, because that “Rock of Israel” could be understood as a reference to Karl Marx. As for the religious writers, they insisted that “Rock of Israel” was insufficient. They wanted it to read: “With faith in the Rock of Israel and its Redeemer.” It didn’t say “God,” but the reference was unambiguous.

Amplifying how deeply divided the two sides were, they could not come up with an agreement even as Ben Gruion planned to declare the state. The proclamation was to be at three o’clock Friday afternoon, a few hours before the British Mandate was to expire (that midnight). Even with this hard deadline, they could not straighten out this passage and get the declaration of independence approved!

Here is how Ben Gurion pulled it off, as he later wrote. The committee finally agreed to add, “And its Redeemer” (a single word in Hebrew: v’goalo) – but it never made it in to the final draft. Ben Gurion claimed the word somehow got lost.

Although this seems like a minute point, this vignette is indicative of a problem that has not been settled to this day. And it may take nothing less than the Messiah to set the record straight. What is the purpose of the Jewish state? How shall it be a “light unto the nations”? What is its soul?

This is an ongoing dilemma. In a positive sense it forces Jews to look at the hard issues and examine the nature of Jewish history and destiny; to think about who they are, what they represent, where they want to go, etc.

The problems of the modern state make the Jewish people more troubled and concerned, but also more creative. Necessity is the mother of invention. Sometimes when there is no choice it forces people to discover surprising reservoirs of creativity they had no idea existed.

That is one way to reframe the disunity and discord that has haunted the Jewish people since the formation of the Jewish state – a disunity and discord which remains unsettling even today.