A Christian merchant in 12th century London once remarked, “As long as Isaac of York trusted his brother Jacob of Marseilles, and both of them trusted their cousin Joseph of Jerusalem, all three stood to make a profit.”

That wasn’t true just in the Middle Ages; it was true in the ancient world as well. Back then, everything was paid in coinage, which was a severe hamper on trade. But Jews early on were successful on the silk and spice routes. They had outposts from the Middle East all the way to China, and all because they invented what we today call “letters of credit” or “checks.”

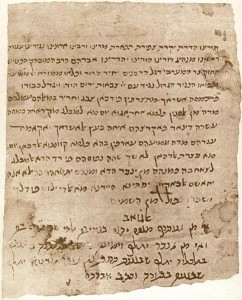

Paper money was first invented by the Chinese in the 11th century, but evidence of the first check came from the geniza of the Great Ezra Synagogue of Cairo, which dates back to the 9th century. A geniza is a storage room where Jews bury holy writings that are forbidden to be thrown out, but people didn’t just use the geniza for holy writings; they put everything there. Some of the items that were found were of enormous scholarship value, and some of them were just ancient grocery lists. Professor Solomon Schechter, under a grant from Cambridge University, identified over 45,000 different items from the Cairo geniza. One was a child’s report card in which the teacher wrote to the parent, “Your child is an underachiever.” They had those, even in the 10th century.

The check found was written by a Jew from Baghdad to a Jew in Cairo, and it read, “Please give Joseph, the bearer of this check, a hundred coins,” and it’s signed. So good old Joseph didn’t have to walk around with a hundred coins in his pocket. He walked around with that piece of paper, which would result in money. That could only work because the Jew in Cairo trusted the Jew in Baghdad. Usually, the Jews involved were related to each other. And that is why that 12th century non-Jew made that that statement. While everybody else was dragging coinage along with them – and it was dangerous; there were bandits along the way – the Jews carried these “letters of credit.” When a Jew came to Kai Feng, China with a letter from his cousin Solomon in London saying, “Give the guy spices. I’ll settle up with you later,” that was a matter of trust. I don’t think that it is for naught that the American government prints, “In God We Trust” on its bills.

Now as we all know, trust depends upon honesty. Honesty is a given in Jewish Law.

When I first came to Israel to live, my wife and I wanted to carpet one of the rooms in our home. We went to a certain carpet store in Jerusalem owned by a nice Persian Jew. We ordered the carpet, it was delivered, and I paid for it. Everything was fine. We went back to the States for a few months, and when we returned to Israel, we decided to carpet the next room, so I went back to the same store. As soon as I walked into the door, the owner jumped out of his seat like he was electrocuted. He said, “Rabbi Wein, I’ve been looking for you a whole year!”

“Oh, no,” I thought to myself. “The check bounced.”

The man took out his wallet where he had 52 shekel wrapped up in a rubber band with a paper with my name on it. He said, “I refigured the bill. I overcharged you 52 shekel.”

That’s an impressive story, but really, that’s really the way it’s supposed to be. And as we have unfortunately learned in recent times, only within the framework of complete and exacting honesty can the economy function properly.