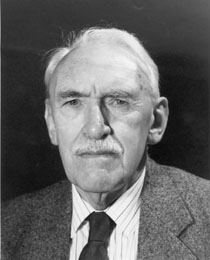

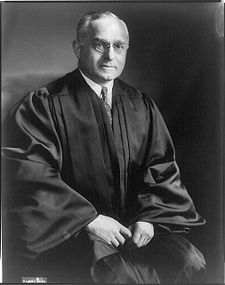

American Jews today take for granted their right to hold high public office, head major corporations, and be enormously influential in every facet of the American scene. But this ready acceptance of the right of Jews to serve on the Supreme Court was certainly not taken for granted in the first half of the 20th century. The first Jew ever appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court was Louis Brandeis. Benjamin Cardozo was the second, but he died after only six years on the bench. With the “Jewish seat” empty, FDR nominated Felix Frankfurter in 1939.

The best way to understand Felix Frankfurter’s judicial and social philosophy is to contrast him with his predecessor, Louis Brandeis. And a fascinating little book called Two Jewish Justices: Outcasts in the Promised Land by Robert A. Burt does precisely that.

When Brandeis was appointed Supreme Court Justice in 1916, he resigned from every organization that he belonged to so that there would be no question of conflict of interest – with the exception of the American branch of the Zionist movement. That was a tremendous departure because until then, prominent American Jews were reluctant about being identified with Zionism. It was seen as dual loyalty and politically dangerous. Yet Brandeis was unafraid about being the spokesman for Jewish causes.

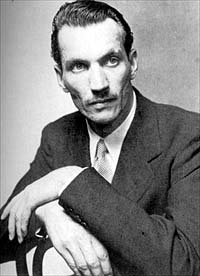

Contrast this with the following chilling anecdote. In 1942, Jan Karski, a fighter in the Polish underground and first eye witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust, secretly came to Washington DC. He met with the ambassador of the Polish government in exile, Ciechanowski, and begged for an appointment with FDR. Ciechanowski could not get the appointment, but instead brought him to Frankfurter.

Karski described what he saw: the round-ups into the ghettos, the starvation and inhuman conditions, the massive shootings, the gassings. He spoke for half an hour, until finally Frankfurter said, “Mr. Karski, a man like me talking to a man like you must be totally frank. So I must say: I am unable to believe you.”

Ciechanowski flew from his seat. “Felix, you don’t mean it! How can you call him a liar to his face?”

Frankfurter replied, “Mr. Ambassador, I did not say this young man is lying. I said I am unable to believe him. There is a difference.”

He picked himself and walked out of the room, and the appointment with Roosevelt was never arranged.

Horrifying as it is for us to think of a Jew in a position of power looking away from the Holocaust, this was a matter of consistency of attitude for Frankfurter. As a justice of the Supreme Court, he consistently sought to protect property, government, and the will of the majority with one notable exception later in his career: in Brown vs. the Board of Education, he urged the court to order desegregation “with all deliberate speed.” All of his life, Frankfurter himself vacillated between viewing himself as an “insider” or an “outsider.” Publicly, he usually assumed “insider” rank and defended the rights of the many against the liberties demanded by the few. But privately, he was nagged by gnawing doubts about his true status, especially of his acceptance by the other justices of the Supreme Court. Burt’s book reports that when his colleagues disagreed with him, he viewed it as a personal rebuke and would become bitterly angry. Thus, he had the worst of all worlds, portraying himself in his judicial stances as the ultimate insider, but knowing all the while that his closest colleagues viewed him as an outsider.