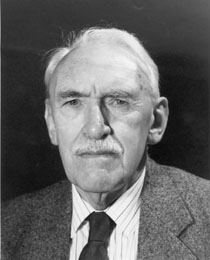

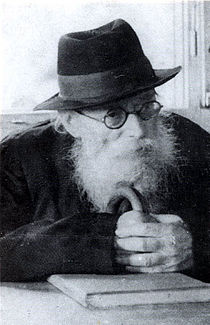

The story of one person’s life often gives insight into an entire historical period, so I want to tell you the story of a man I knew when I was a pulpit rabbi in Miami Beach. His name was Rabbi Grunwald, and he was a Holocaust survivor, originally from Rumania. He lived most of the year in Toronto, but he used to spend the winters in Miami. And even though he and I dressed differently and probably had disparate views on the world, we struck up a friendship. He was an authority on Jewish Law, and I was fortunate enough to study with him a few hours every day. We used to sit in my backyard between the grapefruit and avocado trees in 70 degree weather.

“Miami Beach is the exile,” he’d say, “but if you’ve got to be in exile, it’s not a bad place to be.”

As a Holocaust survivor, he’d already seen the worst places in the exile.

When you learn with someone over a long period of time, you develop a kinship that goes beyond the learning. So after knowing him awhile, I was bold enough to ask, “Rabbi, tell me. How did you get out? What happened to you during the war?”

He was silent for a while, thinking about it, and then he said, “All right, I’ll tell you the story. But I don’t tell it to many people.”

He lived near the border of Hungary and Rumania. The Rumanian army was allied with the Nazis, so he, like many young male Rumanian Jews, was taken into a “work battalion.” These battalions fought with the Rumanian army against the Russians, and they did all the dangerous work, like digging trenches under fire. 80-90% of them were killed within a month or two. They were not trained soldiers, yet they were exposed to all the shelling. It was almost certain death. And he was a delicate person, a scholar. He was not cut out for that kind of work. But he spent a year and a half in the work battalion and survived.

When the war ended, the Russians captured the entire battalion and sent everyone to Siberia. Imagine – the Jews had been forced by the Rumanians to fight, and when the Nazis were finally defeated, the Russians sent them to Siberia as enemies of the state.

Rabbi Grunwald said people were dying like flies. It wasn’t just that they couldn’t take the winter and the malnutrition. They were broken in spirit. During the war, people rallied themselves with the thought, “When the war ends, we’ll get out of this.” But now the war was over, and there was no end in sight. People were just broken.

The commandant of the camp was a Jew. One day, the commandant called him in and said, “I know that you’re innocent, that you don’t belong here. I see what you are; you’re a religious man. But there’s only one way to get out of here. You know Russian. Write a note and address it to Lazar Kaganovich.”

Lazar Kaganovich was Stalin’s brother-in-law, a member of the Politburo. He was also a Jew.

The commandant said, “If you write the note and give it to me, I’ll see that it gets to him. Tell him you were forced into the labor detail, and that you’re on the side of Russia. Tell him.”

Rabbi Grunwald thought about it for two or three days. The penalty for writing a note in the camp was instant death. Perhaps the commandant was playing with him. He’d write the note and then get shot for it. But he didn’t expect to survive much longer anyway, so he wrote the note and gave it to the commandant.

A month passed. Two months passed. Four months passed. Then one day, an official car drove into the camp, and a high-ranking NKVD officer came out of it. All the prisoners in the camp were lined up. The officer said that he had orders from higher up that Prisoner Number – he read Rabbi Grunwald’s number – was there in error and was to be freed. But he said he would not let him go until he found out who smuggled the note out of the camp.

Rabbi Grunwald wasn’t going to tell, but the NKVD general waited for his answer for a week. Rabbi Grunwald kept saying he didn’t know. “What note?”

“Kaganovich – he got a note from you.”

“I know. I saw it.” But he claimed he didn’t know from anything.

After a week, they put him on a train and pushed him off at the Russian-Rumanian border. From there he got to a DP camp, and ultimately, he ended up in Canada.

“Do you know what that story is?” he said. “That camp commandant probably killed thousands of people. But he saved my life . . . for no reason. And Kaganovich! Why did Kaganovich stick himself out for me?”

This story tells us what European Jewry looked like in 1946 and ’47 – broken, subject to all of the whims and vagaries of the great powers, without any place to go. But recovering from the worst brutality possible, Rabbi Grunwald retained his faith and integrity. And that strength and tenacity is the secret of Jewish survival.