After the calamities of the Middle Ages, particularly the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Jewish scholars began to re-examine the meaning of exile. The very concept underwent an evolution. Originally, exile was seen starkly as a punishment for sins. The Books of the Prophets, at least superficially as the masses understood it, explain it that way – it is like a prison sentence. The guilty person serves his time, and when it’s over he goes home.

That argument is easy to maintain for a short exile, like the first Babylonian exile, which lasted 70 years. But in the Middle Ages, that explanation was more difficult. What sin of the Jewish people was so great that it required such a long, bloody and painful exile – with seemingly no end? The Jews may have sinned, but if we compare the Jews’ behavior to many other nations and religious groups in history, it is difficult to place them at the bottom of the ladder. We are not found to be that wanting morally or spiritually. The punishment seems disproportionate to the sin.

This sums up the core problem of Jewish history. Why are we so persecuted? What spiritual purpose does it serve? What purpose does this exile accomplish? If the exile lasts another hundred years, will we become better?

This was an issue that has gnawed at Jewish thought for the last 500 years. It’s not such a problem to us since we live in relative comfort and serenity, even if it’s false serenity. The experience of the exile, certainly inAmerica, is pleasant. But to Jews who had experienced the Spanish Inquisition and Expulsion, to Jews who had experienced the pogroms or the Black Death, to Jews who had been driven from their ancestral homes in Bohemia and Switzerland by the 30 Years War, etc. it was a very real problem.

At least part of the popularity of Kabbalah lay in the fact that it gave answers to these problems, albeit of a supernatural nature. The exile was transformed from being viewed as a punishment for the sins of the Jewish people into a vehicle for redemption (personal, national and global); only through darkness could light shine.

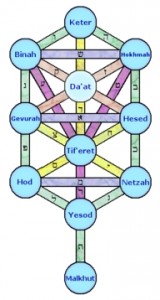

Jews were in exile to extract the “sparks of holiness” scattered throughout the earth, to extract sparks of goodness that lay with the souls of the people of the non-Jewish nations; to gather them together, build them into holiness and transport it all back to the corporate body of Israel, the Jewish people. We were in exile to achieve self-perfection; exile was part of a positive, creative and ultimately redemptive process.

This understanding breathed new purpose into the experience of exile. The Messiah was on his way; at any moment he could burst through. A Jew, even suffering in exile, thus inspired felt that he was engaged in a holy endeavor. As with all holy endeavors it could be costly and painful, but it would lead somewhere better and even utopian. There was no questioning the length of it, because it would take as long as needed to complete the process.