History is made up of all sorts of interesting twists of fate, and the story of the development of Jerusalem is full of them.

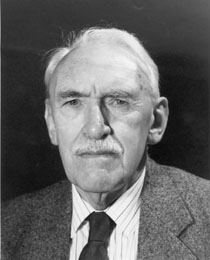

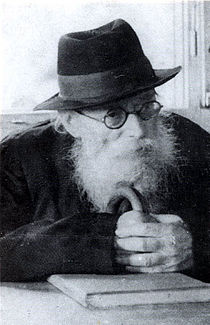

It began with the “chance” meeting of Sir Moses Montefiore and Rabbi Shmuel Salant in Damascus. Sir Montefiore had just made his historic visit to Damascus to advocate on behalf of the Jews imprisoned in the Damascus blood libel. Rabbi Salant, originally from Eastern Europe, was en route to Jerusalem to make a new home for himself. From this “chance” meeting grew a friendship that would bring about the entire development of the city.

Sir Montefiore was a trustee of the will of the great Jewish philanthropist, Judah Touro. He passed away in 1854, leaving $300,000 to Jewish charities – an enormous sum in those times. The will specified that $50,000 should go to benefit the Jews of the city of Jerusalem, but it did not say precisely how. So with $50,000 burning a hole in his pocket, Sir Montefiore visited his friend Rabbi Salant in Jerusalem. The rabbi advised that they buy land outside the walls of the Old City because the Old City was getting too crowded.

Sir Montefiore approached a certain Arab about the purchase of the land and made him an enormously generous offer. The legend is that the Arab refused, saying, “I’ll never sell this land out of my family. I’ll give it to you, Sir Moses Montefiore, but I won’t sell it to you.”

Sir Montefiore was astute enough to know that this Arab wasn’t interested in giving the land away. So he approached him a second time, a third time, and a fourth time until finally the price hit the critical mark and the Arab said, “I won’t sell it, but if you’ll give the money toward ‘a good cause,’ then I’ll ‘give’ the land to you.”

Those were the terms on which the deal was struck.

The land he bought was right outside the walls of the Old City, 18,000 dunam in size, and they named it Neve Shaananim. The next neighborhood Sir Montefiore bought was called Yemin Moshe, named in his honor. There he built the famous windmill, which is still a tourist attraction today. Unfortunately, it has never been anything more than that. The plan was that it would be a grain-milling station that would provide employment for people, but the builder failed to realize that a windmill in dry, landlocked Jerusalem does not work the same way as the mills on the coast of Holland.

The problem was that the Arabs in those times were much like the Arabs now. Jews could not go out safely at night. People were reluctant to move out of the Old City, where they were protected by the walls. That was the significance of the name “Neve Shaananim,” which means “the home of those who are at peace.” In reality, after the apartments were built and the first settlers went to live there, the danger was so real that people would go to the new city during the day so that there would be a Jewish presence there, but at night, they would return to sleep within the Old City walls. And since Jerusalem was under the control of the Ottoman Turks, there were no policemen for the Jews to appeal to. Therefore, it was not until 1872 that a group of seven young families agreed to buy land outside the walls and actually sleep there at night. That neighborhood is called Nachlat Shiva, “the inheritance of the seven.” It was no-man’s land between 1948 and 1967, but it was the first Jewish presence that took hold outside the Old City.

Another great accomplishment of this remarkable team was the founding of Jerusalem’s first hospital, Bikur Cholim Hospital. Sir Montefiore purchased the building and supplied drugs and equipment from Europe, items which were scarce if not non-existent under the Ottoman Empire. And the hospital proved its worth in 1866 when there was a terrible cholera outbreak in Jerusalem in which hundreds of people died. The hospital tended to Jew and Arab alike, though it was primitive medicine. In fact, for the first thirty years, the hospital did not even have a registered doctor, but it was still some sort of place for the sick. It exists today, though no longer in its original location in the Old City. It is best known for its neo-natal unit.

Sir Montefiore, Rabbi Shmuel Salant, and the rabbi’s son Binyamin Beinish continued to develop Jerusalem for the rest of their lives. In fact, in 1909, months before Rabbi Salant passed away, he laid the cornerstone for the Jerusalem neighborhood of Shaarei Chesed, where I live now. He was old, weak, and blind, but he would not miss the dedication of a new neighborhood. And that was their life’s work; under them, Jerusalem multiplied a thousand fold. Without them, it would not be what it is today.