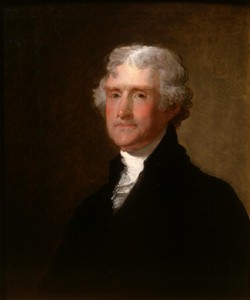

This post concerns Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, seminal contributor to the Constitution, and third President of the United States. He was so towering an intellect that when President Kennedy hosted the 1962 Nobel Laureates at the White House, he said, “This is the most extraordinary collection of human knowledge that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

This post concerns Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, seminal contributor to the Constitution, and third President of the United States. He was so towering an intellect that when President Kennedy hosted the 1962 Nobel Laureates at the White House, he said, “This is the most extraordinary collection of human knowledge that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

What is much less known about Jefferson is that he had a great connection to the Jewish people, and to appreciate this, we first have to understand the prevalent attitudes toward the Jews at the time.

The founding fathers were people of tremendous vision who wanted to try a new experiment in government, a nation without monarchy. And because they had seen how religious warfare racked England, they also had a healthy antipathy toward organized religion.

Of all the founding fathers, Jefferson was the fiercest fighter of religious intolerance. In his home state of Virginia, for example, he repealed “the Law of Disabilities for Dissenters and Jews,” a carry-over from English rule that limited Jews and dissenters (meaning Protestants that aren’t “my kind” of Protestant) in property rights and banned them from holding public office. To the Jews, this was not a major issue; they were accustomed to legal disabilities. As long as nobody was making pogroms against them, they felt they were ahead of the game. They didn’t care that they couldn’t serve on the Virginia House of Burgesses. But what was no problem to the Jews was a problem for Jefferson, not so much because he loved the Jews – he had hardly any contact with them – but because he had not led the revolution to have a country that enforced legal disabilities against minorities.

Jefferson replaced that law with a new bill, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the precursor to the Bill of Rights. He considered this bill one of the major accomplishments of his life. The epitaph on his gravestone, which he wrote himself, reads: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia.”

But his “test case” for religious tolerance was not Virginia, but Maryland. Maryland was founded as a haven for Catholics, but Section 33 of its Constitution read: “the State grants equal and religious rights to all persons professing the Christian religion.”

That law went unchallenged until 1818 when Maryland legislator Thomas Kennedy proposed to amend it to read “all persons” and not “all persons professing the Christian religion.” Thomas Jefferson came to Maryland to lobby with him. But revered a figure as he was, the bill lost by a margin of 50 to 24.

Kennedy and Jefferson refused to give up the fight, and in 1819, the bill was reintroduced and lost again. It lost in 1820, 1821, 1822. . . They reintroduced it every year, and it lost each time. Even when Jefferson’s health began to fail, he continually bombarded the legislature. He felt that if Maryland would rescind the law, no other state would again dare to have such a clause in its Constitution, and his idea of religious freedom would be attained. Interestingly, he did not pursue it in the Supreme Court. He did not want the Court forcing it upon the people; he wanted the people, or at least their legislators, to change their minds.

In 1824, Jefferson took a different tack. He approached Maryland legislator William Worthington with the argument that Jews in other states were building up the economy, and if Maryland continued this discrimination, it would be economically crippled. That argument won the day, and in 1824, the Maryland Constitution was amended so that equal and religious rights were granted to all persons, period.

Jefferson saw that as one of his major victories. He felt that the treatment of the Jews was the true test of how much America really meant “all men are created equal.” In that way, the Jews were the forerunners of all other minorities in America. It is therefore not difficult for us to appreciate his pride in obtaining rights for Jews. That guaranteed that the ideas he wrote into the Constitution were actually followed in practice.