Just as with Rashi, it is impossible for the Jewish people to have existed without the great Rabbi Moses ben Maimon a/k/a Maimonides a/k/a the Rambam. He is called “the great eagle” because he carries us on his shoulders. The epitaph on his grave reads “From Moses to Moses, there arose none like Moses,” and it is no exaggeration. The Rambam’s influence on the Jewish people approached the influence of Moses himself.

It is superfluous to say that the Rambam was blessed with a superior mind. By the time he was 15, he had acquired a complete education. He was, if we can use the term for a person of the 12th century, a renaissance man. The Rambam was not just a Talmudic scholar, but a philosopher, an astronomer, a mathematician, a physician, a linguist, a poet, and a critic. And he was entirely self-taught.

In the year 1150, when the Rambam was only 15, an event occurred that not only had tremendous bearing on his life, but on all of Spanish-Jewish history. The Moslems controlled Spain at that time, and for the first 400 years that the Jews were there, they lived in peace and comfort because the ruling party did not take Islam all that seriously. But as Bernard Lewis points out in his books on the history of Islam, the Moslem religion, like many others, swings like a pendulum between two extremes: the moderates and the fundamentalists. We have seen that swing in our times, and we know how dangerous it is. Similarly, in the Rambam’s times, a sect of Moslems called the Almohads, “the devotees of Mohammed,” gained control of the Rambam’s home city of Cordova. One of their first acts was to force the Jews of Cordova to convert to Islam. If they refused, they had to leave, which meant leaving behind their homes, their furniture, essentially all their wealth. They could only take whatever possessions they could carry.

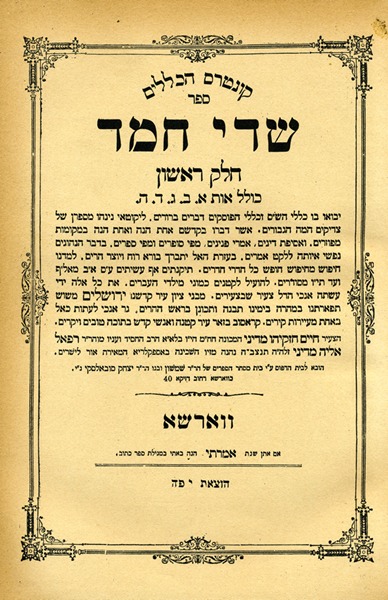

The Rambam and his family fled, and they were so frightened that the Almohads would sweep all of Spain that they left the Spanish peninsula, crossed the Mediterranean, and settled in Morocco. When they arrived in Fez, an Almohad revolution broke out there, too, so they escaped to the Atlas Mountains where they lived in a cave for seven to nine years. Incredibly, during that time, the Rambam wrote the first of his three great works, which was eventually published when he settled in Cairo at age 24. Any one of the Rambam’s works by itself would be enough to guarantee him immortality, but the three together raised him to the gargantuan stature that he occupies today.

The book, like all of the Rambam’s works, was innovative to the point of being revolutionary. First, he wrote it in Arabic. The Jews of Spain and Morocco spoke, read, and dealt in Arabic, just as we deal in English. The prayers and synagogue rituals were in Hebrew, but it was not the spoken language of the people.

His second innovation was to sum up the basic theology of the Jewish people. This may not sound like an innovation, but Judaism is not big on theology in the way Christianity and Islam are. If you scour the entire Talmud, you will find very little of what can be termed theology. But the Rambam felt that the Jews of the time needed a philosophical basis for understanding Judaism.

His third innovation was to tie this philosophy to the observance of the law, which makes him quite different than Rashi. Rashi explains the text, but he does not tell us what laws we can deduce from it.

As often happens in history, whenever someone comes up with something new, there is a strong reaction. Often, the more innovative and positive, the stronger the reaction. So while the Rambam reigns supreme in our time, during his lifetime and a century after his death, he was considered so controversial that his books were banned and even burned. He likewise had supporters who defended him with tremendous ferocity. But the ultimate testament is that after 800 years, his works remain indispensable in the study and practice of Jewish law.

For more about Maimonides, please check out our film Rambam: The Story of Maimonides.