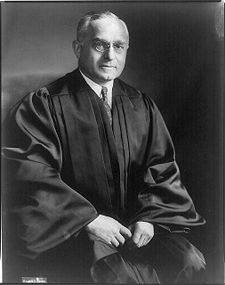

With the recent appointment of the first Latina to the American Supreme Court, it is worth remembering the first Jewish Justice, Louis D. Brandeis, who was appointed by President Wilson in 1916. Like with Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Brandeis’ appointment was a great symbol of “arrival.” It brought more pride to the Jewish community than did the election of Jews to high public office. Elections are decided by votes, and there were many Jewish voters. But an appointment to the Supreme Court was a matter of presidential nomination and senatorial confirmation, an acknowledgment by non-Jewish society of the value of the Jewish contribution to America.

Louis Brandeis’ family arrived in America with the first wave of Jewish immigrants in the year 1850. Like most Jewish immigrants of the period, they originated from Germany and did not observe Judaism, though the family never denied its Jewish ethnicity. However, Brandeis had an uncle named Lewis Dembitz who was an observant Jew and a powerful role model in his life. He was a lawyer with a sterling reputation and was also an ardent abolitionist. Brandeis’ decision to pursue a career in law came from the direct influence of this uncle. He so admired him that he even changed his middle name from David to Dembitz.

Though Brandeis himself was never an observant Jew, he described the impression that his uncle’s religious behavior made upon him:

“. . . I recall vividly the joy and awe with which my uncle, Lewis Dembitz, welcomed the arrival of the [Sabbath] day and the piety with which he observed it. I remember the extra delicacies, lighting of the candles, prayers over a cup of wine, quaint chants and Uncle Lewis poring over books most of the day. I remember more particularly an elusive something about him, which was spoken of as the ‘Sabbath peace,’ and which years later brought to my mind a passage from Addison in which he speaks of stealing a day out of life to live. That elusive something prevailed in many a home in Boston on Sunday and was not wanting at Harvard on that same day. Uncle Lewis used to say that he was enjoying a foretaste of heaven. I used to think, and do so now, that we need on earth the Jewish-Puritan Sabbath without its oppressive restrictions.” (Strum, Phillipa. Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984, page 11.)

What he failed to appreciate is that the very presence of the “oppressive restrictions” is what makes the Jewish Sabbath “a foretaste of heaven.”

Naturally, Brandeis’ appointment to the Supreme Court did not happen without bitter opposition. Anti-Semitism was rife at that time, and Brandeis’ Jewishness was an issue in the Senate confirmation hearings. Even when he was finally appointed, his colleague Justice McReynolds refused to say one word to him in his entire 23 years on the Court. Nine people in one room, deciding on the most important cases on the country, and one wouldn’t speak to the other.

Because of this, Brandeis identified with the outsiders of society. A forerunner of the Warren Supreme Court, he was the first to articulate the solicitude a democracy should show to the disadvantaged and the individual, as opposed to protecting the rights of the insiders and the Establishment. In this, he was truly a Jewish justice, in the tradition taught by the great Hillel: “One should not judge someone else unless he is capable of standing in his place.” (Ethics of the Fathers 2:4) His utopian dream resonates with the vision of the Hebrew Prophets and the Talmudic heritage of justice. He was an heir to it, albeit unknowingly so.