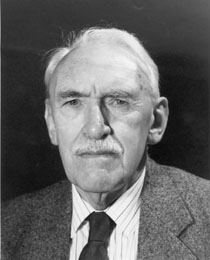

I know that it sounds strange but Herman Wouk is an important person in my life. I met him only three times in my life and probably we exchanged no more than twenty words between us in all of those meetings. Wouk passed away at the age of 104 on May 15, 2019 but remarkably in 2012 at the age of 97 produced another novel that was published by Simon and Schuster. This book, The Lawgiver, is a wry look at Orthodox and secular Jewish life in America, the Hollywood movie industry and at Wouk himself and his wife of sixty-three years who was his literary agent as well. Wouk’s wife Betty Sarah, passed away in her ninetieth year. The Lawgiver is written as a series of memos, emails, letters and recorded conversations between the characters presented in the book.

As in all of Wouk’s works there is plenty of insightful humor present on the human condition and the foolish foibles of human beings, even of paragons of faith and religious observance. After all, Wouk was one of the gag writers for the famous radio comedian of seventy years ago in the United States, Fred Allen. But Wouk’s primary influence on me stems not from his written words, engaging and talented as they are, but rather from a speech that he delivered over sixty years ago to a banquet of the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago, a banquet I attended (but did not have a place setting or food there). He had just received fame as prizewinning author and playwright and was outed to the general American public as somehow being a practicing Orthodox Jew. In those days such a successful American Jew who still observed the Sabbath and ate only kosher food was a rarity. And his speech at that banquet was masterful in delivery and content.

He predicted the wave of assimilation that would overtake American Jewry in the coming decades and warned that if there were no spirituality or traditional observance, no love of Torah or of Israel present in the coming generations they were doomed to disappear from Jewish life and history. I had never heard anyone put forth the case for traditional Jewish life and values so ably and bluntly. I said thank you to him after the speech as I stood in line at the dais with hundreds of others, many of whom asked him to sign copies of his book that they had brought along. The speech inspired me then and continues to inspire me now. It strengthened my then youthful and perhaps even naïve belief that Orthodoxy was the only way to go even in America and that I should somehow contribute to its defense and growth.

I met Wouk again at a Sabbath synagogue in Palm Springs, California where he then resided. And I met him for a third time in Yemin Moshe in Jerusalem where he owned a home and partially resided. He had vaguely heard of me and was courteous to me. I reminded him of his speech in long ago Chicago and he ruefully smiled and said: “them were the days!” And I thanked him for writing the seminal “This Is My God,” a book that I have used and given to others countless times in my long rabbinic experience and career. This book, above all others that he has penned will surely stand the test of time and changing literary tastes and forms.

At the conclusion of The Lawgiver, Wouk has written an epilogue about the characters in this novel. In concluding the epilogue itself Wouk wrote a beautiful, heart-wrenching farewell to his wife. He wrote: “We shared our time under the sun for sixty-three years, during which I did all my literary work. Before we met I wrote nothing that mattered. Whoever reads a book by Herman Wouk will be reading art deeply infused with her self-effacing and incisive brilliance, books composed during a long literary career managed by her common sense, with which I am sparsely endowed.

Here is Betty Sarah Wouk, the girl I met by God’s grace in 1944, a Phi Bete and an enchantment, working in Navy personnel. She rests in peace beside our firstborn son, who accidentally died in Mexico when almost five years old. My place at Abe’s other side awaits me in God’s good time.”