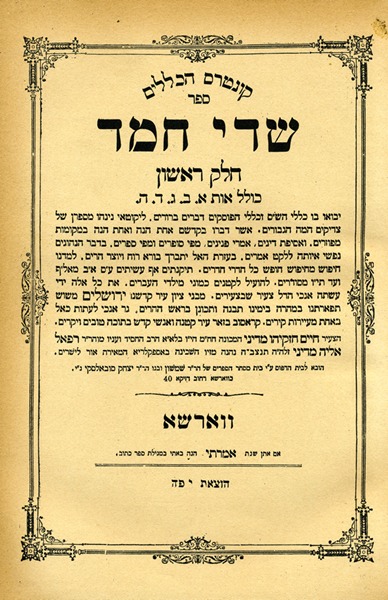

Rabbi Yechezkiya Chaim Chizkiya Medini (1813-1905), author of the Sdei Chemed, was not only a great scholar and genius but father of the modern Torah encyclopedia. His life spanned many lands, touching all types of Jews and even non-Jews.

He was born in the Old City of Yerushalayim, which at the time housed a large Sephardic population – “large” meaning maybe 800-1,000 in 1813. The Sdei Chemed’s father, Rabbi Rafael Medini, was a long-time settler in Yerushalayim. He traced his lineage back generations upon generations. According to some scholars, the name Medini comes from the word medina and indicated that the person was a legal resident. Jews were often denied permission to live in Jerusalem. Those who did were called “Medini,” signifying that they had the legal right to live there.

Rabbi Rafael Medini’s son, Yechezkiya Chaim Chizkiya, earned a reputation among both the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim in Yerushalayim by the time he was 10. He was raised and taught by his father; he never went to a formal yeshiva.

He married before his bar-mitzvah, at the age of 12. This was not unheard of among the Sephardim. In Yemen, some married as early as 10 or 11. His father supported him in his learning, enabling him to learn until he was 19.

Then, suddenly, his father died. At that time, not only did he feel the yoke of earning a living for his wife and himself, but for his widowed mother and his younger brothers and sisters as well. He tried his hand at a number of trades: he was a textile broker/merchant, but that failed; he tried to deal in wheat and grain, but that failed. The Jews in Jerusalem did not have an economy to speak of.

After about a year and a half, he was penniless. The Sephardic rabbi in Jerusalem, Rabbi Chaim Abulafia, discovered that the Medini family had relatives in Constantinople. He recommended the young man leave Jerusalem and go to Constantinople.

He did so and was helped by his relatives until he contracted typhoid fever and was on the verge of death. He lived in a quarantined area for a number of months, hovering between life and death.

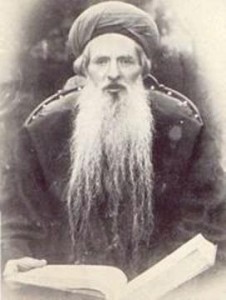

After recovering, he became a private tutor to wealthy Jews for the next 13 years until 1867. People actually waited in line to study with him. In 1867, a wealthy Jewish merchant from Crimea came to Constantinople and met Rabbi Medini, who in addition to being great scholar was handsome, tall, with striking eyes and a long beard. He looked the part of the holy man. Even the Arabs would come to see him; his visage represented holiness to them too.

This wealthy Jew told him that the Jews in Crimea had not had a Rabbi in 40 years. He told him that even though the Jews there knew very little about Judaism, they wanted to be Jewish. If he would come, the community would support him and help him make a spiritual revolution in the Crimea. The man pressed the Rabbi every time he visited Constantinople until he finally consented.

He came to a city in the Crimea called Karasubazar (modern day Bilohirsk) and became the Rabbi — the only one in the entire Crimea. He stayed for 33 years and brought a spiritual revolution to the Jews there. He opened schools and raised the level of understanding of the tradition. He was a remarkable force.

In 1887, the anti-Semitic Czarist government in Russia, which had since invaded and taken over Crimea, told the influential Rabbi Medini that he had two weeks to leave the Crimea. Through a long series of appeals, the Jews were able to postpone this decree for 12 years, but in 1899 he had no choice but to leave.

By now, he was world-famous and was wanted back in Constantinople. He was also offered a rabbinate in Baghdad and other places in the Sephardic world. Nevertheless, he said that his last desire was to return to the city of his birth, to Jerusalem. He also said that if he would return to Jerusalem, he would not return as Chief Rabbi, but as a simple Jew. In his words, “I only want bread to eat and cloth to cover my nakedness. I am not interested in honors, position or in wealth.”

We have a description of the scene. The entire Jewish community of the Crimea, which numbered close to 30,000 people, came to the docks to see him off. They wept openly. They saw in him their father, their mentor, their attachment to everything that was holy in their tradition. It Finally, he boarded a boat on the Black Sea and departed.

Crimea had lost its father, but Jerusalem would get back a lost son.