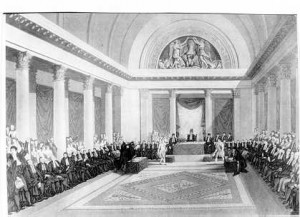

In 1807, Napoleon attempted to revive the Great Sanhedrin, the Supreme Court of the Jewish people in Biblical and Talmudic times, but which had been disbanded centuries earlier due to persecution. Preparatory to its convening, Napoleon convened a “Council of Notables.” He put before this Jews “Council of Notables” a series of 12 questions:

- Is it lawful for Jews to have more than one wife?

- 2. Is divorce allowed in the Jewish religion, and if it is, is it allowed even in contradiction to the codes of French law?

- 3. Does Jewish law permit a Jewess to marry a Christian man, or a Jew to marry a Christian woman, or may they marry only other Jews?

- In the eyes of Jews, are Frenchmen who are not Jewish, considered to be their brethren or strangers?

- What type of conduct does Jewish law prescribe toward non-Jewish Frenchmen?

- 6. Do the Jews who are born in France, and have been granted citizenship by the laws of France, truly acknowledge France as their country? Are they bound to defend it, to follow its laws, to follow the directions of the civil and court authorities of France?

- 7. Who elects rabbis?

- What kind of judicial power do rabbis exercise over the Jews?

- 9. If there is rabbinical jurisdiction over the Jews, is it regulated by the laws of the Jewish religion or is it merely a custom existing among Jews?

- 10. Are there professions from which Jews are excluded by Jewish law?

- 11. Does Jewish law prohibit Jews from taking usury from other Jews?

- 12. Does Jewish law prohibit Jews from taking usury from non-Jews?

Napoleon did not just have a passing interest in these questions or the Jews under his control. He had a program of assimilation for the Jews and expected the Council to provide him with pat answers that would make it seem as if they were agreeing with his program. The Council, indeed, prepared answers in keeping with Napoleon’s wishes. They were not about to risk their necks. Additionally, many of them truly believed in Napoleon’s program to assimilate the Jews.

For example, as far as divorce was concerned, they answered that it was valid in Jewish law only if it was also approved by civil authorities—thereby saying that in a country that banned divorce, such as Italy, Jews would never get divorced. That was a patently false answer, because Jews who had lived in Italy for hundreds of years had been granted divorces all through that time. Nevertheless, that was the answer Napoleon wanted to hear, because it was the answer that said the Jewish religion was subservient to the State and would not do anything against the wishes of the State.

Similarly, for each question, they provided the answer Napoleon wanted, not necessarily what Jewish law required. Napoleon hoped that their answers would help him structure Jewish life so that all the intermarriages would be recognized, so that Jews would spread into all professions and move to all parts of the country, and so forth. In short, he hoped that through his program, within a generation the Jewish communities under his control would be decimated and Jewish authority—especially religious authority—would be undermined.

Though Napoleon’s Great Sanhedrin failed, his goal to assimilate the Jews of Europe gained traction during his time.