The major revolution within traditional Jewish life and society occurred in the first part of the eighteenth century with the advent and rise of the Chassidic movement. Founded by the mystical and in his time relatively unknown Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the movement represented a major rebellion against the then current religious establishment and power structure of Eastern European Jewry. Chassidus emphasized prayer and piety, social concerns and economic justice as being equal if not even superior to Torah learning itself.

The major revolution within traditional Jewish life and society occurred in the first part of the eighteenth century with the advent and rise of the Chassidic movement. Founded by the mystical and in his time relatively unknown Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the movement represented a major rebellion against the then current religious establishment and power structure of Eastern European Jewry. Chassidus emphasized prayer and piety, social concerns and economic justice as being equal if not even superior to Torah learning itself.

The strength of Chassidus lay in the fact that it was able to attract a very high caliber of people as its leaders. At the same time, it was able to appeal to the masses of the Jewish people as its followers.

After the death of the Baal Shem Tov, the leadership of the movement splintered among his disciples but eventually Rabbi Dov Ber, known as the Maggid of Mezeritch, became recognized as the most prominent leader of his time. He taught, trained and guided a large number of great men who became leaders in their own right, conducted their own courts and spread Chassidus and its ideas throughout Eastern Europe.

However, from the beginning the opposition to Chassidus was very strong, and almost all of the great early Chassidic Rebbes suffered severe persecution. The strength of the opposition – the Misnagdim — lay in the fact that Chassidus was revolutionary, radical and Kabbalistic. It came after the time of Shabbetai Tzvi and other false messianic movements — which were also revolutionary, radical and Kabbalistic — and therefore the establishment saw it as having dangerous tendencies.

One is tempted to say that it is really the Misnagdim who saved the Chassidim from themselves. The Misnagdim, by their strong and persistent opposition, by pointing out the failings of individual Chassidim and of Chassidus generally, brought to the attention of Chassidus the areas in which it had to seek improvement, and it is that which guaranteed that Chassidus would modify to a certain extent any of its most extreme positions and remain within the mainstream of Jewish law and the Jewish people. It is to their credit, therefore, that they paid attention and listened to their enemies.

Desperately Seeking the Gaon

As long as Rabbi Elijah Kramer, the Gaon of Vilna was alive, the opposition to Chassidus was very firm, strong and fierce. The followers of the Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid attempted many times to mollify the Gaon, but he would not meet with them. The first Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, was a great Torah scholar and philosopher, and the prime defender of Chassidus against the Misnagdim. He wrote that he attempted many times to arrange a visit with the Gaon in Vilna, but he could never get his foot in the door. The Gaon refused to see him.

The Gaon did not want to meet the Chassidic Rebbes, because he did not want to give them the opportunity to say they had met with him and proved their case. Also, the Gaon did not want to violate the terms of his own decree of excommunication, which included the prohibition against social dealings with Chassidim.

After the death of the Gaon, even though the disagreement was not over completely, the bitter events would soon fade. The Misnagdim no longer placed a greater emphasis on fighting the Chassidim than they did upon building their own strength and their own institutions. The Chassidim forced the Misnagdim to adopt some of the Chassidic ideas, to reform themselves from the charges made against the Misnagdim, that they were cold and that they were elitists with no connection to the masses. The Chassidim forced the Misnagdim to rethink that, just as the Misnagdim forced the Chassidim to answer the charges that they were not scholarly and did not observe Jewish law and gave more attention to externals than to real service of G-d, etc. Ironically, it almost became a symbiotic relationship, wherein each one needed the other.

The Chozeh

After the death of the Maggid of Mezeritch there arose one of the great leaders of Polish Chassidus, the man who was called the “Chozeh [Seer] of Lublin.” He was given that name in recognition of the fact that people held him not only to be a miracle worker, but a prophet capable of seeing into the future.

His name was Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz. He lived in Lublin, where the rabbi of the town gave him a great deal of opposition. Nevertheless, Lublin turned into a center of Chassidus.

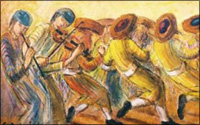

The Chozeh preached a simplified, almost supernatural understanding of life and of Judaism. The emphasis was on prayer services with song and joy, convivial meals and drinking, fabulous miracle tales about the Rebbe and the belief that being attached to the Rebbe provided an attachment to God Himself. It was under his reign and direction that Chassidus accomplished its almost complete spiritual and political conquest of Eastern European Jewish life and society. Jews by the thousands flocked to Lublin to see the Chozeh and be seen by him and others. The movement was now a full-fledged mass populist tidal wave that forever changed the face of Eastern European Jewish life.

In the history of revolutions, the revolution must revolt against itself lest it become frozen into the establishment. After Chassidus became a mass movement, a certain section of that leadership became disenchanted. They thought there had to be better things to do than spend the day discussing the problems the Jewish peasant was having with his cows. Or they became turned off to the miraculous, supernatural aspect of Chassidus and smarted under the accusation of not being Torah scholars in the same rank as the leaders of the Misnagdim.

This opened the door to yet another revolution within the revolution.

Psyzcha

A new revolution brewed within Chassidus. It was touched off by one of the students of the Chozeh of Lublin, Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowitz. He was called the Yid Hakadosh, “the Holy Jew.” His brilliance in Torah and his holy personality instantly made him a magnet for young men in Poland seeking the inspiration and spirituality of Chassidus.

The Yid Hakadosh longed for a more intellectual and scholarly approach, a synthesis of great Torah scholarship with holy piety and impassioned prayer. After a number of years of soul searching and grappling with his own inner truths the Yid Hakadosh broke with Lublin and left to form his own small and elite court in the town of Psyzcha (Peshischeh).

There he collected around him a cadre of scholars and geniuses who accomplished the synthesis that the Yid Hakadosh longed for. Devoted to the truth as they saw it, unsparing in criticism of self and others, the group in Psyzcha soon became the target of the adherents of the Chozeh and of the followers of other mainstream traditional Rebbes who were working with the masses. The deviations of Psyzcha from traditional Chassidus philosophy and practice brought about charges of heresy against the court of Psyzcha. But the Yid Hakadosh and his followers never wavered in their attempt to reach heaven through the dual –and to them, joined — parallel paths of intellectual Torah creativity and selfless piety and prayer. This revolution was to make Chassidus deeper instead of wider, to have a smaller group rather than a larger audience, and to have an elite group rather than the masses.

One of the main students and followers of the Yid Hakadosh was Rabbi Simcha Bunim. He succeeded the Yid Hakadosh as the leader of Psyzcha after his death. The Rebbe, Reb Bunim, as he was called, had come to Chassidic leadership after traversing a far different road than the traditional one of so many Rebbes. Simcha Bunim had a fluent knowledge of many languages, was skilled in secular studies, served as a land and port agent in the then German city of Danzig, attended the theater, played cards and was a licensed druggist. Even upon his return to Poland he continued to dress in Western short suit style and not in the long caftans that were the traditional uniform of Polish Chasidim.

Nevertheless, he became a great Rebbe with wide ranging influence over all of Polish Chassidus. He was successful in attracting the best and brightest of Polish youth to Psyzcha and to convince them to adopt his ideas and programs. Thus Psyzcha can be viewed as the successful counterrevolution within Chassidus that outdid the original revolution in scope, influence and intensity.

Kotzk

When Reb Simchah Bunim died, the revolution reached its height by the choice of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Morganstern of Kotzk, “the Kotzker.”

He was a great genius and Torah scholar, but even more than his predecessors he was a harsh searcher for truth no matter the personal cost and controversy engendered thereby. In spite of his absolute loyalty to truth to the point of being unable to abide fools or liars — or perhaps because of it — he became the most popular Rebbe in Poland, with thousands flocking to Psyzcha to be challenged by him. He intended to have only a few Chasidim follow him and to help Psyzcha become a truly elitist court. However, his very fame destroyed this dream of his and he became terribly frustrated by this very “success” of popularity.

For almost the last 20 years of his life he remained mainly in seclusion, but even that did not stop the flow of visitors and new adherents to Psyzcha.

His main disciple, Rabbi Mordecai Yosef Leiner, broke with the Kotzker and founded his own court in Izbiztcha. His dynasty of Chassidic leaders was known as the Chassidus of Radzin.

After the death of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Morgenstern, Psyzcha declined and new Chassidic courts – Vorki, Alexander, Gur, etc. – came into being to fill the void. They were all influenced by Psyzcha, but they all drew back from the extreme goals and actions of Psyzcha. The revolution was over and normative Chassidus, much as we know it today, took hold. It became the establishment and no longer the revolution. It would become the bulwark of traditional defense against assimilation, secularism and to a great extent secular Zionism as well. It would thereby become the target of ridicule and scorn of the secularists in Jewish life.