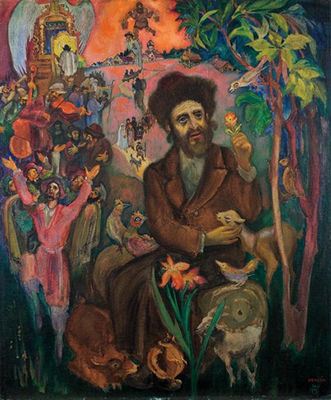

In previous generations, some of the most pious Jews would leave their homes and cities to wander from city to city. They disguised themselves as ordinary beggars, took a walking stick and traveled from one Jewish community to the next. They did this in order to suffer the ignominies of exile. The practice of voluntary exile is mentioned by Maimonides (Laws of Repentance 2:4), who writes that it atones for a person’s sins. However, other reasons are suggested by various commentators, including feeling the pain of the Shechinah (Divine Presence), which is in exile, and to attain a truer picture of the world.

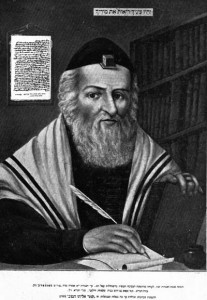

The legendary 18th century genius of the Jewish people, Rabbi Elijah Kremer, the “Vilna Gaon,” was the greatest Talmudic mind of many centuries, past and present. His immense scholarship and rigorous intellectual discipline influenced almost all of the later commentators to the Torah text until our day. When he was in his twenties he undertook a personal exile time. It is not clear whether the Gaon did so for three or five years. Either way, he did not advertise that he was the renowned scholar he already was and he was usually not recognized as such. However, on some occasions he was discovered. The rabbi of the town saw that this was no ordinary beggar.

There are numerous legends about the Gaon in exile. One is that he came to a town and a rabbi invited him to stay in his house overnight. The Gaon asked if he had any books and rabbi answered that he had only one book, the commentary of the Rashba, a great 14th century Talmudic commentator. The rabbi did not know that he was hosting the Vilna Gaon, and gave him the Rashba so as not to embarrass the poor, ignorant beggar. The Gaon took the book and studied it all night. The next morning he returned it to his host, thanked him and mentioned that the last two pages had been missing but he had written them out for him.

In his wanderings, he attempted to discover not only rare manuscripts but rare people — those whom he felt had potential for Torah greatness. Many times there are great people who find themselves in small and unknown communities. They can easily become discouraged and feel that they are never going to get anywhere. The Gaon looked for such people and attempted to strengthen them in knowledge of the Torah.

In the course of his travels, the Vilna Gaon once asked his gentile wagon driver to stop at the side of the road so that he could daven. As he was praying, the wagon driver whipped the horse and disappeared in a cloud of dust, taking with him all of the Gaon’s meager possessions. He was stranded with absolutely nothing to his name – nothing, that is, except for his prayer.

Think about this story the next time you travel. You land in an airport and wait for your luggage to appear on the carousel. You follow the bags as they revolve upon the carousel until your neck is sore. Then when the last piece of luggage has been removed and your battered suitcase is nowhere in sight, you trudge down endless corridors to the lost-and-found. They tell you that your luggage has gone to Omaha. You are not in Omaha.

How will you react? Will you get angry? Or will you say, “Ahah! That is what happened to the Vilna Gaon. I am in exile just like him.”

That is when you can begin to identify with the Creator. The airline can take everything away from you, but your connection to the Shechinah stays with you. Instead of feeling humiliated by your helplessness and dependency, you will come to see it as a way of connecting to God.