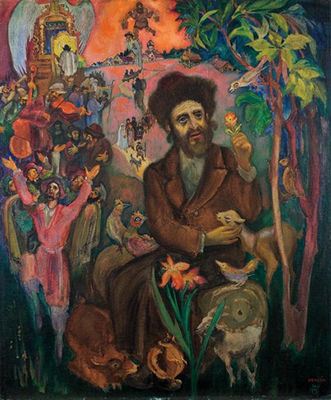

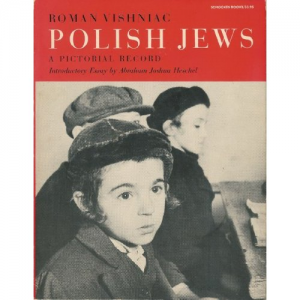

Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote an introduction to Roman Vishiniac’s photographic record of Eastern European Jewry before the Holocaust called Polish Jews. It is a description of Jewish life in the shtetl:

There was scarcely a house in all the kingdom of Poland where its members did not occupy themselves with some study of Torah. Thus, there were many scholars in every community. With the coming of dawn, the members of the chevrah Tehillim, a group devoted to reciting the Book of Psalms, would rise to recite the psalms for about an hour before prayers. Each week they would complete the entire recitation of the Book of Psalms. And far be it that any man should oversleep the time of prayer in the morning, for there was a beadle assigned to the task of knocking on the window shutters of all homes.

One did not miss going to the synagogue except for very unusual circumstances. No disputes among Jews were ever brought before gentile courts or before a nobleman or even before the king. And if a Jew did take his case before a non-Jewish court he would be severely chastised and criticized.

All of the pillars upon which the world rests – Torah, prayer, charity, truth justice and peace — were in existence in the Jewish communities in the kingdom of Poland. To be sure, in the life of Eastern European Jews, there was not only light but also shadow. Though there was learning, there was also a neglect of manners, discourtesy, and provincialism. In the crowded conditions in which they lived, persecuted and tormented by ruthless laws, intimidated by drunken land owners, despised by the newly enriched city dwellers, trampled by the boots of the police, chosen as scapegoats by political demagogues, the rope of self-discipline sometimes snapped.

In addition, Jews lived among naked misery and frightful poverty. And this deafened the demands and admonitions of religious enthusiasm. The regions of piety were at times too lofty for ordinary mortals. Not all Jews could devote themselves exclusively to the Torah and service to God. Not all old men had faces of prophets. There were not holy men and kabbalists, but also yokels, beggars and tramps.

There were many who lived in appalling poverty. Many were pinched by the never-ending worries and there were plenty of taverns available with strong spirits. But drunkards were almost never seen amongst Jews. When night came and a man wanted to while away his time, he did not hurry to the tavern to take a drink. He went rather to his books or joined a group that even with or without a teacher gave itself over to the pure enjoyment of study. Physically worn out by their days of toil, they nevertheless said over open volumes and intoned the austere music of the Talmud.

Poor Jews whose children knew only the taste of potatoes on Sunday, potatoes on Monday, and potatoes on Tuesday, etc. sat like intellectual princes. They possessed whole treasuries of thought, and the knowledge, ideas and sayings of many sages. When a problem came up, there immediately was a crowd of people to offer opinions, proofs, and quotations. One raised a question on a difficult passage in Maimonides’ works and many vied in their attempts to explain it, outdoing one another in the subtlety of dialectic distinction. The stomachs may have been empty, the houses overcrowded and poor, but the minds were rich and replete with the riches of the Torah.

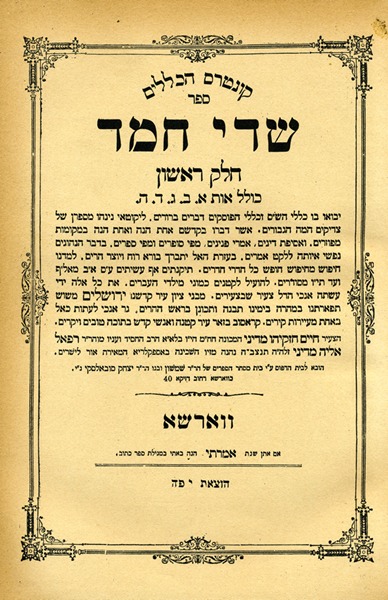

That short description of Eastern European Jewry is certainly accurate as to the Jews who lived in the 1600s in Poland, Lithuania and Russia. It was a time of enormous scholarship. The commentaries to the Shulchan Aruch were all then being written and proposed. It was a time of stability in the Jewish community.

But this was the calm before the storm — and the storm would brew an enormous terrifying hurricane that would engulf the Jewish people.