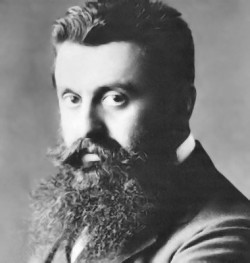

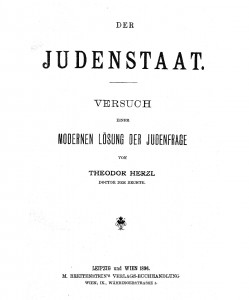

Theodore Herzl is considered the founder of Zionism. He is the one who convened the First Zionist Congress in 1897 and declared, “Today I have founded the Jewish state. It will take you 50 years to see it.”

However, long before then the idea of Zionism was in the air. It had been growing in Eastern Europe with the Lovers of Zion movement, which was begun by religious Jews and based on a religious impulse. Others also began taking up the mantle of the idea of a Jewish state. Herzl, therefore, was not the founder of Zionism so much as someone who rode the wave that already was in motion. He directed, publicized and gave it a formal voice, but the idea and impetus were there before him.

For instance, in 1825, there was an American by the name of Mordecai Manual Noah, a very wealthy Sephardic Jew who had been the American consul in Tunis. Upon his return he purchased an island in the Niagara River right near the Niagara Falls. His plan was to take that island, Grand Island, and make it a Jewish state. He renamed the island Ararat after the mountain that Noah’s ark rested upon. His idea was to offer a resting place and refuge for all the downtrodden Jews the world over.

He was not alone. Other Jews had ideas about bringing their fellow brethren to such places as Argentina, Chile, North Dakota and New Jersey. Of course, the Lovers of Zion were religiously motivated to set up a Jewish state in Palestine. The common denominator of all these thoughts, nevertheless, was that to save the Jews you had to get them out of Europe.

An eccentric Englishman man in the 1850s named Sir Laurence Oliphant (1829–1888) was struck with the idea that England should take over Palestine and give it to the Jewish people, protecting and training the Jews, and ultimately providing them with their own national home. There was also a body of British Christians who believed, much as the Southern Baptists in the United States believe, that in order for the Second Coming to occur the Jews first had to return en masse to the Land of Israel. This will help explain the Balfour Declaration in 1917. There had long been Christian Zionists, so to speak, advocating for it.

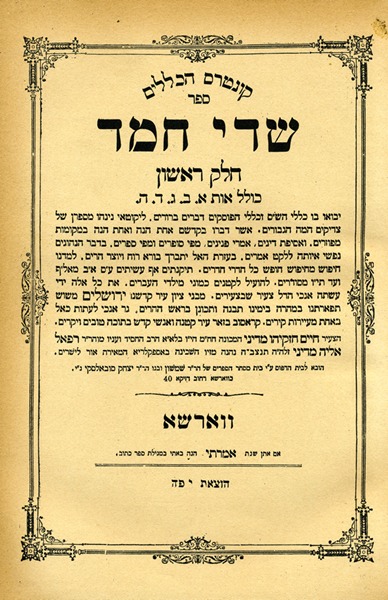

Two books made a great impression on the pre-Zionist movement. Moses Hess’ Rome and Jerusalem, and Leon Pinks Auto Emancipation, were early tracts strongly advocating action toward establishing a Jewish state. Similarly, George Eliot (a male pen name for Mary Anne Evans) wrote a famous novel called Daniel Deronda in 1876. It was sympathetic toward the Zionist idea 20 years before Herzl!

All these examples amply demonstrate that for a long time there had been a climate for Herzl’s idea. Collectively, these voices concluded that somehow the time was ripe for the Jewish problem to be solved – and the best way to solve it was by giving Jews their historical homeland.