History tends to judge people far differently than their contemporaries do. Many people who were considered to be outstanding and influential in their lifetimes are lowered in the run of history. And many people who suffered indignities in their lifetimes are raised generations later. We just have to wait a while for the verdict to come in. This post will explore two people whose lives illustrate both sides of that coin.

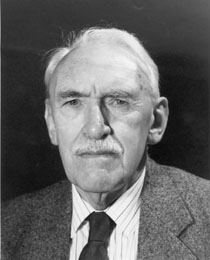

The father of Reform Judaism was Moses Mendelssohn. He a short, unattractive person – a hunchback with the stereotypical hooked Jewish nose. The Prussian emperor said about him, “Never have I seen such great wine in such an ugly vessel.” Mendelssohn was a genius: a graduate of the highest German universities, an author of philosophy books, and friend of the Crown Prince of Prussia. Yet at the same time, he was a profound Jewish scholar and Talmudist who communicated with the leading rabbis of the day.

Mendelssohn proposed that every Jew should “be a cosmopolitan man in the street, and a Jew at home.” In other words, Jews should give up their traditional garb and dress like Germans. They should stop speaking Yiddish. But in their homes, they should still keep kosher, and observe the Sabbath, etc.

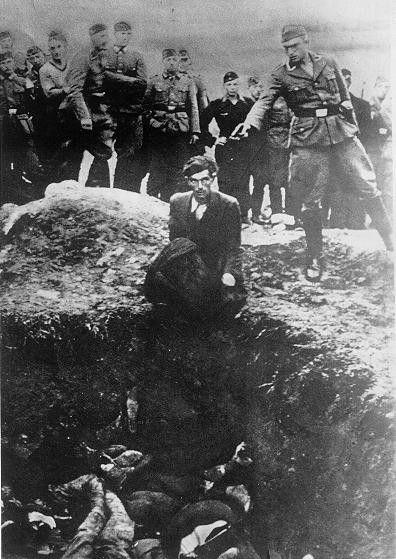

This was a fatal mistake, and a typical one for a genius: the belief that everyone else is just like him. Mendelssohn assumed that all Jews could repeat this matchless trick of being simultaneously respected in both traditional Jewish and German intellectual circles. But his ideas were an abysmal failure, even in his own family. Four of his six children converted to Christianity. When Jews began abandoning Jewish customs in the street, they abandoned Jewish practice in their homes as well. This occurred on a massive scale throughout Germany, and contrary to what Mendelssohn thought, the more the Jews became like Germans, the more the Germans despised them.

Because of this, certainly amongst traditional Jews, Moses Mendelssohn is now viewed not only persona non grata, but as a traitor, someone who opened the door to the Holocaust. In many religious Jewish homes, even the mention of his name is forbidden, let alone the reading of any of his works.

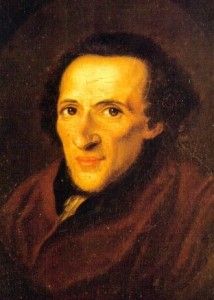

The precise opposite of this happened with Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, also known by the acronym, the Ramchal. Like Mendelssohn, he lived in the 18th century, but unlike Mendelssohn, he was an outcast in his lifetime. He was a Kabbalist at a time when Kabbalists were persecuted, and so his life was tragic. His books weren’t just ignored; they were banned. He himself was excommunicated several times, first in his native Italy, and then in France. He fled to Amsterdam and found work as a lens grinder, but his enemies pursued him. He emigrated to the land of Israel, and then died in a cholera epidemic at the age of 39.

With such a short life, we shouldn’t know anything about him, but history stepped in and “rehabilitated” him. It began after his death when his writings were recognized by the leader of the Jewish people, the Gaon of Vilna. It culminated when his books were accepted as central texts in the mussar yeshivas whose main focus was character perfection. Today, his books are studied universally throughout the traditional Jewish world. But I would hazard to say that most people don’t realize how controversial they were in his own times.

So we can say that history has voted for the Ramchal and against Mendelssohn. The verdict has come in. History gets the last vote in a person’s ultimate legacy.