While Jews in Eastern Europe remained relatively insulated from outside influence, Jews in Western Europe were affected by an internal schism within Christianity that set into motion forces which are still not spent; forces which changed forever the face of civilization, which ushered in the beginning of the modern Western world.

While Jews in Eastern Europe remained relatively insulated from outside influence, Jews in Western Europe were affected by an internal schism within Christianity that set into motion forces which are still not spent; forces which changed forever the face of civilization, which ushered in the beginning of the modern Western world.

The Catholic Church had hit upon hard times in the middle Ages. It suffered from its own particular brand of success: it was too large, too powerful and too wealthy. Then a monumental split occurred between the French Popes in Avignon and the Roman Popes in Rome that left tremendous scars within the Church and among the masses. When the schism was followed by a serious of amoral Popes – e.g. the Borgias and Medicis – it undermined the Church in the most profound ways.

Even though the Church allegedly took the vow of poverty it was an ideal that was unrealized. In its pursuit of money and to finance its various projects, the Church severely taxed all of Europe. St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, as one example, is not understated. The opulence of Christian Europe was built upon the backs of its parishioners.

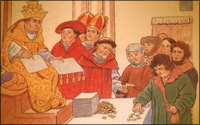

The Church had various schemes for raising large amounts of money, but the one that damaged its reputation most was the sale of indulgences.

The Sale of Indulgences

In Church theology, all of the saved Christians in history earned “credit” in heaven. When they died they did not need all the “credit” they had accumulated. Therefore, all of the “extra credits” became the property of the Church. Since the Church had this vast storage house of good deeds it could help people who lacked them, who on their own do not have enough “credits.” And those credits could be purchased for money from the Church. This process became known as the “sale of indulgences.”

This created a situation where the worse a person was spiritually the better he was for the Church. And because he was so indulgent in evil deeds he probably had the wherewithal to pay for indulgences.

This theology had always existed in the Church, but grew out of control in the late 1400s and early 1500s. The primary impetus for this was that there were various projects that needed money. The main projects included the Basilica (St. Peter’s) and the Sistine Chapel, along with all of the artwork. They needed a tremendous amount of money, a great proportion of which was collected from the sale of indulgences.

When there is a lot of money floating around there is going to be corruption. Money does not bring out the best in people, even if they are monks, friars, priests, bishops, cardinals, etc. The corruption was of such a nature that it became a mockery in Europe.

The sale of indulgences undermined the basic idea of the Church. Why did one need good deeds if one could buy one’s ticket to heaven? For all practical purposes the prevailing philosophy became, “Eat, drink and be merry, because tomorrow you’ll buy an indulgence and be ready to die.” This situation ran contrary to any of the moralities that the Church hoped to represent.

Martin Luther

There had been attempted rebellions against the Church throughout the ages, beginning with the Gnostics in the 6th century. However, now there arose an enemy that the Church was not able to put down. History clothed him in the person of Martin Luther, a German monk.

He had been forced into religious life by his parents, who literally sold him to become a monk. He had a keen mind, vaulting ambition, great talents – and an inherent hatred for authority. He was constantly in trouble with his superiors in the Church.

In Germany, friars actively went from town to town selling indulgences, sometimes keeping 90% of the money for themselves. Everyone – from the local Church to the district bishop — got paid off along the way. The pie was cut into many pieces in order for everyone to cooperate.

Martin Luther could not stand it.

He had other quarrels with the Church. Christianity, he said, was built on inner faith and not subservience to the Church in Rome. The inner faith of the Christian, which would bring him peace and tranquility, was the ticket to heaven. That inner faith, he claimed, was built upon Scripture. Since most of the Catholic world was illiterate – at least as far as Latin was concerned, and the only Bibles were in Latin – they had in effect shut out its believers from ever knowing anything about the Bible.

Luther solved that by translating the Bible into German. To us, a German translation of the Bible does not sound revolutionary. However, in the 16th century it was. It had always been in the interest of the organized Church to keep the Bible a sealed book. In the Middle Ages that was easy to do because most of the people were illiterate. But once people could read it in their native tongue there was room for a different interpretation. Therefore, the single act of translating the Bible into German served to break the power of the Church over its people.

The power of the printed Bible is not to be underestimated. It can be a more powerful weapon than a canon.

The 95 Theses

In 1517, Martin Luther challenged the Church by nailing to the door of the Cathedral at Wittenberg his now famous “95 Theses,” i.e. questions regarding the Church – none of which was very revolutionary at the time. Nevertheless, the overreaction of the establishment guaranteed the success of the revolution. Had the Church chosen to ignore it, people would have thought Luther was just another crazy monk. However, they did not let it go, and gave fuel to his movement.

The local bishop immediately relieved him of his duties and sent a report to Rome, demanding that Martin Luther be excommunicated. Luther, who had as sharp mouth as he did a pen, traveled throughout the towns of Germany stirring up controversy, one the established Church could not back down from. The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V called Luther to trial at the Diet of Worms, where the parliament met. He was allowed to defend himself, which was a mistake because his articulate defense of his ideas damaged the Church as much as anything.

Thus, the schism began.

All of the malcontents, including the peasants and lower classes, who had nothing to lose, joined in the revolution. It started in Germany but spread throughout Europe. Luther himself became much more radical, including abolishing the institution of celibacy for the clergy and marrying a former nun.

In short, he founded a new religion. The religion, however, took on different forms. In Germany it took the form of what became known as the Lutheran Church. In Switzerland, John Calvin introduced what would become known as Calvinism. In England, Henry VIII used it as an excuse to divorce Catherine and marry Ann Boleyn – which he later regretted. In France, it was the Huguenots who revolted.

Martin Luther’s revolution ignited one of the most destructive conflicts in European history, the Thirty Years War. In truth, although it was allegedly between the Protestants and the Catholics it had many overtones. All of the age-old hatreds in Europe boiled into this cauldron of conflicting theologies.

Luther and the Jews

Regarding the Jews, Luther made the same mistake Mohammed made. He was certain that the Jews would support him and even become Lutherans. He had shaken the Church to its core, withstood excommunication and stood up to the Holy Roman Emperor. He thought he was so special that the Jews would convert.

His early letters in the 1520s regarding the Jews are extremely positive. He said, for instance, that the Jews were the only ones who properly saw the ills of the Church. It’s no wonder that they rejected the Pope and never became Catholics.

However, he was not even rebuffed – he was ignored. The Jews in Germany were not interested in becoming Protestants or getting drawn into the vortex of forces warring in Europe. Furthermore, a much more radical element within Protestantism arose, the Anabaptists. They said the problem with Luther was that he was not Protestant enough!

This type of dynamic happens in all revolutions: the next generation is more radical, making the previous generation look moderate. Eventually, the revolution runs its course and the radicals are seen for what they are. The Anabaptists believed that one had to be baptized again as an adult. Some became absolute pacifists. It’s from them that the Amish, Mennonites, Quakers, Shakers and Puritans evolved. To them, Luther was little more than a wayward Catholic disguised as a Protestant.

Luther was not a man who took criticism very well – especially from people whom he felt he was owed a debt of gratitude. Consequently, he unleashed a particularly vituperative verbal assault against his Protestant enemies. In the blindness of his fury, he unleashed it on the Jews as well, saying things that made their way directly into anti-Semitic Nazi hate-literature. Some articles in Julius Streicher’s Der Sturmer — the leading Nazi propaganda paper — were verbatim quotations from Luther.

In effect, he transferred a great deal of the anti-Semitism in the Roman Catholic Church into the Protestant Church. Originally, the latter attempted at least to say it would do away with the bigotry of the former. In one of Luther’s early writing he freed the Jews, so to speak, from the accusation of deicide, which in the 1500s was an enormous act, not matched by the Vatican until 1963. Nevertheless, by the end of his life he had reverted to terrible anti-Semitism – which he spared no opportunity to express and verbalize.

The Jews suffered terribly even though the Thirty Years War was a war ostensibly only between Catholics and Protestants. It led to chaos and anarchy. Armed bands marched around looting and killing without any force to stop them. By the end of the war, the Jews much preferred to be in areas under Roman Catholic control, which more or less protected them. In Protestant areas the Jews were left to the wrath of the mob.

Jewish life in Germany, France and the Netherlands suffered terribly. The physical ravages were enormous. Jews would rebuild themselves in the 1600s but they would never again be able to make Western European Jewry the leader of world Jewry. That is why after this period the entire picture of Jewish life shifts to Eastern Europe: to Poland, Lithuania and Russia – where the Protestant Revolution did not reach.

Similarly, later the Age of Emancipation and Reform did not reach Eastern Europe. To a certain extent neither did the Industrial Revolution. It was as if there was an iron wall serving as an actual line of demarcation between Western and Eastern Europe.

In the writings of rabbis from Western Europe during this time they wrote about chaos, war, uncertainty and suffering. But in the writings of the rabbis of Eastern Europe there was none of that. None of those problems spilled over to them. It was if they were living on two different planets.

Echoes of the Revolution

The Protestant Revolution was the first time in the history of Western Europe that the established Church was thoroughly defeated. True, the Church made a comeback, so to speak, in the Counter-Reformation – in the founding of the Jesuits by Ignatius of Loyola. The established Church cleansed itself of many of the accusations that had been raised against it. Nevertheless, it was too little too late.

From the 1600s on, the Roman Catholic Church never again tried by force of arms to bring the Protestants back into the fold. A tacit understanding existed between the two, which it does until today. That does not mean that there aren’t radicals on both sides that would to destroy each other, but for the most part an unstated peace treaty has remained in place since then.

The defeat of the established Church was not lost upon the Jewish people. In a couple of centuries, a group of Jews would do the same, breaking off from the establishment, claiming to reform Judaism and fix up its problems (notwithstanding the fact that it too would eventually be accused of becoming the establishment and in need of reform). It is no accident that this movement was born in Germany.

After the war, the Jews in Western Europe would rebuild and set up important communities with great rabbis. However, these communities were transient in nature. By contrast, Polish Jews at the time were so rooted to the country that they felt like nothing could ever shake them, that they were going to be in Poland forever. Jews in Western Europe during the 1500s and 1600s, however, did not have that security. They did not take part in the conflicts between the Catholics and the Protestants, but the conflict undermined their own existence and gave them a terrible feeling of insecurity, which would be exploited in the next century.