The forced conversion of a quarter-million Jews in Spain was, in spiritual terms, a Holocaust never equaled in the long exile of the Jewish people. Even under the worst of circumstances of assimilation it never matched the finality of conversion.

The forced conversion of a quarter-million Jews in Spain was, in spiritual terms, a Holocaust never equaled in the long exile of the Jewish people. Even under the worst of circumstances of assimilation it never matched the finality of conversion.

At the heart of the tragedy were the Marranos. These were Jews who had officially converted to Christianity but saw themselves as Jews and practiced Judaism in secret as much as they could. Most Marranos never left Spain and became full-fledged Christians within 50-60 years. Even though Jewish customs were preserved in Marrano homes, sometimes even for centuries – e.g. lighting candles on Friday night or eating unleavened bread with the onset of spring — it was treated by later generations as nothing more than a mysterious family tradition. As far as religion was concerned, they were Catholic.

When expulsion order in Spain went into effect in 1492, many Jews fled across the border into Portugal. But then they were expelled from Portugal five years later. That decree was probably even more damaging to them than the original decree of expulsion from Spain because it indicated that this time the Inquisition-Church-Christian society was far more serious than anything previous.

Within the first 50 years after the expulsion, there was a steady exodus of Marranos from the Iberian Peninsula. However, they had a hard time mingling with their fellow Jews.

Even though the rabbis of times had decreed that Marranos be accepted and taken back into the community, Jews outside of Spain had very little sympathy for the Marranos. For many generations, people would not even marry into their families or treat them as Jewish — mostly out of resentment that when the moment of truth came they opted to convert rather than take upon themselves the privation of exile.

As a result, many Marranos formed their own communities and remained isolated. Either way, the reaction among the Jewish people was extremely negative toward the Marranos.

Italy

The establishment of the Jewish community in Poland, in the 1400s and early 1500s, formed the center for Ashkenazic Jewry. However, Sephardic Jewry, having been expelled from Spain, made for itself different homes throughout Europe and the Mediterranean basin.

Italy was a prime landing place. Even though it was nominally the most Catholic country in the world, Italy was divided into many small kingdoms. Compared to the Church in Spain, the Church in Italy was liberal. It was the time of the Medici and Borgias popes who, to put it bluntly, were not religious.

Many Marranos found a home in Italy. It was there that they were most accepted by the Jewish communities.

The most famous Jew to flee there was Don Isaac Abarbanel. His presence in Italy gave standing to the Spanish Jews, and even to the Marranos, who rose rapidly to positions of wealth and influence.

From the middle of the 1500s onward, the Italian-Jewish community was really a Spanish community. Nevertheless, around the same time the Abarbanel arrived, a great rabbi from Poland settled in the town of Padua, Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen. He had three ones: a rabbi, a banker and a merchant. They befriended Italian noblemen scattered among the fractured states of the Italian peninsula and created a base for Jewish life for the future.

Rabbi Katzenellenbogen and his sons fathered a great number of descendants. Similarly, there are hundreds of descendants of Don Isaac Abarbanel. These two great rabbis, more than anyone else, literally created the Italian-Jewish community and were the cement that held it together.

When the Marranos came to Italy they brought with them certain non-Jewish traits that wended their way into the greater Jewish community. For instance, the great synagogue in Florence, which was built during that time, resembles a church in terms of architecture. By contrast, the Spanish-Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam exhibits traditional Jewish-synagogue architecture. While in no way flamboyant on the outside, on the inside it has famed eastern mahogany imported from Brazil. Furthermore, great engineering went into it, as it was built on the canal and its foundation rests on wooden poles that allow it to move with the tide. Nevertheless, even though it is an historic building, it is not an impressive building from an architectural standpoint.

By contrast, the synagogue in Florence is a magnificent piece of Renaissance architecture. However, it greatly resembles the style found in non-Jewish houses of worship. The Marranos brought that with them.

Turkey

The second place the Marranos came to was Asia Minor, which today includes Turkey, Greece and Salonika.

The Marranos actually followed the path of migration that Sephardic Jewry in general undertook after the expulsion from Spain. From Turkey, Greece and Salonika they eventually came to Syria and Aleppo.

The Jews came first to Constantinople (today Istanbul), meaning the Jews were back under the rule of the Muslims. The Muslims never gave them an easy time, but they never destroyed them either. It was not a comfortable exile, but it had less ups-and-downs than the Christian exile.

The founder of Turkish Jewry was Rabbi Elijah Mizrachi, famed for his super-commentary to Rashi on the Pentateuch. His family did not originate from the Spanish exile, but he rallied Spanish Jewry around him. When the Marranos came he was able to assimilate them into the Turkish community and they were accepted more than any other place in the world.

Rabbi Mizrachi was the central rabbinic figure and is regarded as the foundation of Turkish Jewry. He buttressed the Sephardic customs and liturgy, which became closer to the Arab liturgy than it had been in Spain, because the Jews now lived among the Arabs. Even though the Turks are not Arabs they dominated the Middle East and now Jewish dress, music and general outlook in life took on the trappings of the country they lived in.

There was also a large Jewish community in Salonika, one of the islands of Greece. That community would be completely destroyed by the Nazis in the Second World War when the 7,000 Jews there were sent to Auschwitz. Nevertheless, Jews had lived there for 400 years. They made a living in boating and fishing – so much so, that it was known among the non-Jews that one could not buy fish on the Sabbath. Even after the Nazi eliminated the Jews, that custom of no boats going in and out of the harbors remained in the non-Jewish community until very recently.

The Land of Israel

The third place that the Spanish Jews and Marranos attempted to escape to was the Land of Israel.

Even though very few Spanish Jews went to Israel, a few hundred families did. It is possible to trace the beginnings of a stronger Jewish presence in the Land of Israel, a presence that has constantly grown since that time until our times, to the Spanish expulsion.

The founder of the Jewish community in Jerusalem was the renowned Rabbi Ovadiah of Bartenura, the man who penned the seminal commentary to the Mishnah still used by everyone who studies it today. He was a Spanish Jew who went to Italy, to the town of Bartenura and then to Jerusalem. He was the rabbi there and set up the Sephardic community.

The second town that the Spanish Jews came to in the Land of Israel was Safed (Tzfas), situated in the hills not far from the Sea of Galilee. It is one of the four holy cities in the Land of Israel, according Kabbalistic tradition (Jewish mysticism). The others are Jerusalem, Hebron and Tiberius.

As elsewhere, the Marranos came to Israel with the Spanish exiles. In the rabbinic literature of the times one can see over and over again the challenges that the presence of the Marranos brought with them.

It was at this time that, in order to differentiate themselves from the Marranos, that the Sephardim adopted a suffix to their name, the Hebrew letters samech and tet (“S” and “T” sounds respectively), which stood for Sephardi tahor, “pure Spanish Jew.” This suffix did not only serve to differentiate them from Ashkenazic Jews but from the Marranos. It was a statement saying in effect, “In this family, there were no Marranos.”

Other Places of Refuge

The Sephardim also escaped to the present-day countries of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, which are right across the Strait of Gibraltar at the southern tip of Spain. There had long been strong Sephardic communities there dating back to the eighth century. In fact, the Spanish Jewish community had originated there. Now, when they returned they rebuilt their communities. The refugees of Spain brought with them the wealth and traditions of Sephardic Jewry.

People like Rabbi Isaac ben Sheshet (1326–1408), known by his acronym Rivash, and other great Spanish rabbis came to Morocco, setting the foundations for the Jewish communities there — communities that would stay intact until being driven out in the early 1950s. The Jews lived in Fez, Marrakesh, Casablanca, Tunis and other cities.

Finally, some Spanish Jews ended up in Egypt. The leader of the Jewish community there was Rabbi David ibn Zimra, the Radvaz. He was the chief rabbi of Cairo and left over for posterity 3,000 legal decisions. He was also a diligent chronicler of the times and the turmoil that existed. However, this community very rapidly assimilated, taking on Egyptian dress and lifestyle.

Holland

In Europe, since the Netherlands belonged to Spain, it was natural for Spanish Jews to immigrate to Holland. The majority of the Jews who fled to Holland were Marranos and they became very wealthy.

More than any other European country, Holland has strong Jewish influences. The city of Amsterdam, with its magnificent canals (similar to Venice), was built by Jews, who made it into the largest port in Europe.

The Jews of the 1500s brought to Amsterdam trade and commerce. The famous Dutch East India Company, responsible for settling so much of what would become America, was financed and headed by Jews; even though they did not take a prominent public role they were the driving force behind it. Indeed, under Jewish influence Holland became a colonial world power, even though in terms of natural resources and population it had no right to be so.

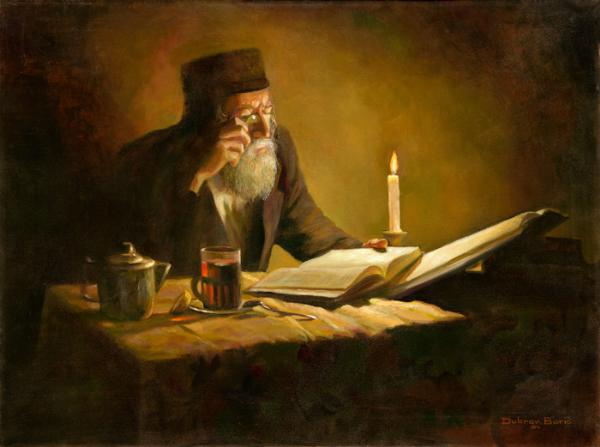

The Jews were the patrons of the famous Dutch masters. That is why so much of the art of Holland is about Jewish subjects. Rembrandt’s portfolio, for instance, includes a surprising amount of works with Jewish subjects. He lived in the Jewish neighborhood and was supported by Jews. Many of his themes included lighting the Sabbath candles, the Jewish bride, the rabbi, biblical “Old Testament” scenes and the prophet Jeremiah. He and a number of other artists were preoccupied with Jewish themes. That is because Jews backed them.

The famous rabbi of Amsterdam in the late 1600s was Rabbi Tzvi Ashkenazi, a world-renowned genius, who had served in Europe beforehand.

Time Heals Wounds

Holland became a world power with the help of Jewish drive and ingenuity. This was mainly the result of the Spanish Jews who had fled Spain, and then the Marranos who followed afterward. Almost all of them officially resumed their observance and practice of Judaism openly. After a period of time they were integrated into the community.

Interestingly, among the things Jews brought to Amsterdam was religious tolerance. In the ancient library next to the Spanish-Portuguese library, in the rotunda, is a membership list from the 1600s. Next to each name is a code noting who was a Marrano and who was not. However, gradually after 50-60 years the code disappears. Everyone integrated.

We see from that how very hard it was for those Jews who gave up everything in Spain to act with complete equanimity toward those Jews who had caved into the pressure and converted. Nevertheless, time would heal the wounds.