The two main pillars on which all of Jewish scholarship rests are Rashi and the Rambam (a/k/a Maimonides). They differed not only on issues of philosophy but in overall style and approach. Part of the reason for this is that Rashi was Ashkenazi and the Rambam was Sephardi. Each was a product of a distinct tradition.

Generally speaking, the Sephardic commentators looked at the broad picture of Judaism, the forest and not the trees. The Ashkenazim, on the other hand, focused more on the trees than the forest. They concentrated on words, nuances, and the nitty-gritty of the Talmudic give-and-take. Therefore, the Rambam’s writings are quintessentially intellectual and philosophical, whereas Rashi’s greatness is his ability to take you through the Torah and Talmud detail by detail, word by word.

These differences did not grow in a vacuum. They developed from specific historical forces. In terms of time, the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities developed simultaneously, but in terms of experience, they lived in two completely different worlds. In order for us to really get a handle on them, we have to look at each one separately.

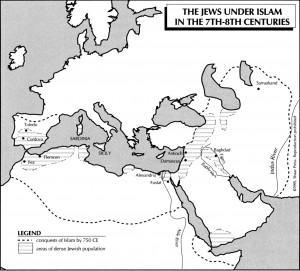

After the Jews were sent into exile in 70 CE, the main Jewish community in the Diaspora was Babylonia. It was the only place in the world where Christianity did not take over, and therefore, the Jews thrived there. They built their own yeshivas and lived autonomously. Thus, they were free to engage in the centuries of scholarship that produced the Talmud.

In the 9th century, the Jewish community in Babylonia began to decline, so many Jews went to North Africa, which was populated by two Moslem tribes: the Berbers and the Moors. The Berbers were fierce warriors, while the Moors were artisans, mathematicians, and merchants – the cutting edge of civilization. Together, they became a tremendous force in the world.

In the 9th century, the Jewish community in Babylonia began to decline, so many Jews went to North Africa, which was populated by two Moslem tribes: the Berbers and the Moors. The Berbers were fierce warriors, while the Moors were artisans, mathematicians, and merchants – the cutting edge of civilization. Together, they became a tremendous force in the world.

The Jews saw they had opportunity with them, particularly with the Moors, who were less religious and therefore, more tolerant. In other Moslem countries where the Jews lived, they had to accept the status of dhimmi, second-rate citizen. Their synagogues had to be unobtrusive, and they had to keep a low profile. All that changed with the Moors. Their alliance with the Jews lasted almost 400 years, and by the time the Moors were emigrating from North Africa into Spain, they brought along the Jews not as dhimmis, but as equals.

Thus, the Sephardic Jews lived in an open and intellectually advanced society. The study of philosophy abounded, so Sephardic Jewish scholarship became philosophical. The Jews also rose in public life, becoming government ministers. Maimonides was court physician to the Sultan of Egypt. Individual Jews sometimes suffered assaults from their Moslem neighbors, but there were no Crusades, no pogroms per se, no Holocaust.

The Ashkenazic Jew, on the other hand, never had a good day. He lived in a primitive world full of constant danger. Western Europe had sunk into the Dark Ages; less than 1% of the population was literate. Even the great king Charlemagne, the first to invite the Jews to Europe, could not sign his own name.

Charlemagne extended his invitation to the Jews with the offer of land, equal rights, and imperial protection. A small group of Jews left Babylonia and settled in the German Rhineland, mostly in the cities of Worms, Speyers, and Mainz. But because the Church converted the native pagans, Christianity became a religion full of superstition and brutality. This, in part, gave rise to the Crusades and the pogroms of the Black Death. It’s mind-boggling that Ashkenazic Jewry survived those early centuries, but not only did it survive, it grew.

So, while the Sephardim viewed their Moslem neighbors as equals, the Ashkenazim looked at their illiterate Christian neighbors with disdain. They led an insular existence, and their sole intellectual pursuits were Torah and Talmud. And this is what accounts for the different traditions and characteristics of Sephardim and Ashkenazim.