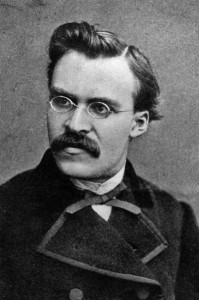

In the late 1800s there arose to prominence a highly influential German philosopher by the name of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). Historians debate how much his writings represent anti-Semitism. On one hand, some of his writings express negative views about Judaism. On the other hand, he was also anti-Christian. In fact, he had worse things to say about Christianity than Judaism. As an atheist he was adamantly against all religion.

At the same time, some of his writings contain repudiations of anti-Semitism. He even went so far as to break off from his publisher for being an anti-Semite and wrote a sharp letter to his sister for marrying an anti-Semite and having anti-Semitic views.

Be that as it may, Nietzsche’s philosophy became a cornerstone of Nazi ideology, particularly his idea of the Übermensch, the Superman. As the Nazis interpreted it, certain races – the Aryan, Germanic race, specifically — were entitled to rule, dominate, lord over and enjoy the fruits of this world more than others. Combined with Darwin’s idea of the Survival of the Fittest, the Übermensch philosophy became a license to conquer, kill and enslave all the non-Germanic races, especially the lowest and most dangerous of them, the Jewish race.

Nietzsche’s writings were also used to paint Judaism as the root of all evil. Nietzsche pointed out that the despised Christian religion had its roots were in Judaism. Ideas such as “Love thy neighbor,” “turn the other cheek,” “be charitable” contradicted the idea of the Survival of the Fittest and the Übermensch. It was for the weak. Again, historians debate the depth of Nietzsche’s animosity toward Judaism; they claim it was really Christianity that he was attacking. But no one debates that the Nazis interpreted his ideas to mean that Judaism was a virus that infected the world. Christianity — and even worse for the Nazis: Communism — was nothing more than a front for Jewish ideas meant to suppress the strong, Germanic spirit.

German 19th century anti-Semitism found echoes is some very strange places. The great German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883), who had a fixation with German and Pagan mythology, was a rabid anti-Semite – and his wife was worse. Some of the otherwise greatest people in Europe subscribed to the vilest racial theories.

The anti-Semitism was not confined to France or England. Henry Adams, one of the famous and influential social commentators in the United States, said he lived only in the wish to see the end of “infernal Jewry.”

Barbara Tuchman’s book, The Proud Tower, is a portrait of the world before the First World War, 1890-1914. The chapter called, “Give Me Combat,” discusses anti-Semitism in Europe at the end of the 1800s. In about 50 pages she provides a remarkably clear idea about the ground swell of anti-Semitism that enabled civilized Europe a few decades later to exterminate six million people without much protest. The way she paints it, the anti-Semitism was so strong and virulent that it was almost a foregone conclusion that it was going to happen.

Her book is well worth reading to anyone who wants to understand the real roots of the Holocaust – roots that still need to be understood in today’s world.